The Flat Earth Theory

A Dome Over A Flat Earth – Everything Is Under Water?

Flat Earth

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about ancient cosmologies in which the Earth was regarded as flat. For the erroneous modern notion that belief in a flat Earth was responsible for a major source of opposition to Christopher Columbus, see Myth of the flat Earth. For other uses, see Flat Earth (disambiguation).

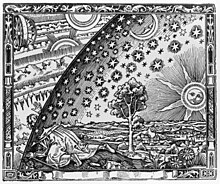

The Flammarion engraving (1888) depicts a traveler who arrives at the edge of a flat Earth and sticks his head through the firmament.

The flat Earth model is an archaic conception of the Earth's shape as a plane or disk. Many ancient cultures subscribed to a flat Earth cosmography, including Greece until the classical period, the Bronze Age and Iron Age civilizations of the Near East until the Hellenistic period, India until the Gupta period (early centuries AD) and China until the 17th century. That paradigm was also typically held in the aboriginal cultures of the Americas, and the notion of a flat Earth domed by the firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl was common in pre-scientific societies.[1]

The idea of a spherical Earth appeared in Greek philosophy with Pythagoras (6th century BC), although most Pre-Socratics retained the flat Earth model. Aristotle accepted the spherical shape of the Earth on empirical grounds around 330 BC, and knowledge of the spherical Earth gradually began to spread beyond the Hellenistic world from then on.[2][3][4][5]

Historical development

Ancient Near East

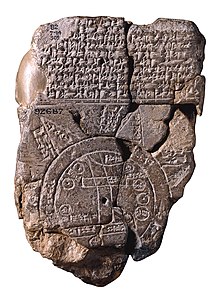

Imago Mundi Babylonian map, the oldest known world map, 6th century BC Babylonia

In early Egyptian[6] and Mesopotamian thought the world was portrayed as a flat disk floating in the ocean. A similar model is found in the Homeric account of the 8th century BC in which "Okeanos, the personified body of water surrounding the circular surface of the Earth, is the begetter of all life and possibly of all gods."[7] The Israelites likely had a similar cosmology, with the earth as a flat disc floating on water beneath an arced firmament separating it from the heavens.[8]

The Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts reveal that the ancient Egyptians believed Nun (the Ocean) was a circular body surrounding nbwt (a term meaning "dry lands" or "Islands"), and therefore believed in a similar Ancient Near Eastern circular earth cosmography surrounded by water.[9][10][11]

Ancient Mediterranean

Poets

Both Homer[12] and Hesiod[13] described a flat disc cosmography on the Shield of Achilles.[14][15] This poetic tradition of an earth-encircling (gaiaokhos) sea (Oceanus) and a flat disc also appears in Stasinus of Cyprus,[16] Mimnermus,[17] Aeschylus,[18] and Apollonius Rhodius.[19]

Homer's description of the flat disc cosmography on the shield of Achilles with the encircling ocean is repeated far later in Quintus Smyrnaeus' Posthomerica (4th century AD), which continues the narration of the Trojan War.[20]

Philosophers

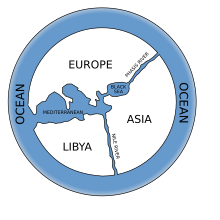

Possible rendering of Anaximander's world map[21]

Several pre-Socratic philosophers believed that the world was flat: Thales (c. 550 BC) according to several sources,[22] and Leucippus (c. 440 BC) and Democritus (c. 460 – 370 BC) according to Aristotle.[23][24][25]

Thales thought the earth floated in water like a log.[26] It has been argued, however, that Thales actually believed in a round Earth.[27][28] Anaximander (c. 550 BC) believed the Earth was a short cylinder with a flat, circular top that remained stable because it was the same distance from all things.[29][30] Anaximenes of Miletus believed that "the earth is flat and rides on air; in the same way the sun and the moon and the other heavenly bodies, which are all fiery, ride the air because of their flatness."[31] Xenophanes of Colophon (c. 500 BC) thought that the Earth was flat, with its upper side touching the air, and the lower side extending without limit.[32]

Belief in a flat Earth continued into the 5th century BC. Anaxagoras (c. 450 BC) agreed that the Earth was flat,[33] and his pupil Archelaus believed that the flat Earth was depressed in the middle like a saucer, to allow for the fact that the Sun does not rise and set at the same time for everyone.[34]

Historians

Hecataeus of Miletus believed the earth was flat and surrounded by water.[35] Herodotus in his Histories ridiculed the belief that water encircled the world,[36] yet most classicists agree he still believed the earth was flat because of his descriptions of literal "ends" or "edges" of the earth.[37]

Ancient India

Ancient Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist cosmology held that the Earth is a disc consisting of four continents grouped around a central mountain (Mount Meru) like the petals of a flower. An outer ocean surrounds these continents.[38] This view of traditional Buddhist and Jain cosmology depicts the cosmos as a vast, oceanic disk (of the magnitude of a small planetary system), bounded by mountains, in which the continents are set as small islands.[38]

Norse and Germanic

The ancient Norse and Germanic peoples believed in a flat Earth cosmography with the Earth surrounded by an ocean, with the axis mundi, a world tree (Yggdrasil), or pillar (Irminsul) in the centre.[39][40] The Norse believed that in the world-encircling ocean sat a snake called Jormungandr.[41] In the Norse creation account preserved in Gylfaginning (VIII) it is stated that during the creation of the earth, an impassable sea was placed around the earth like a ring:

...And Jafnhárr said: "Of the blood, which ran and welled forth freely out of his wounds, they made the sea, when they had formed and made firm the earth together, and laid the sea in a ring round. about her; and it may well seem a hard thing to most men to cross over it."[42]

The late Norse Konungs skuggsjá, on the other hand, states that:

...If you take a lighted candle and set it in a room, you may expect it to light up the entire interior, unless something should hinder, though the room be quite large. But if you take an apple and hang it close to the flame, so near that it is heated, the apple will darken nearly half the room or even more. However, if you hang the apple near the wall, it will not get hot; the candle will light up the whole house; and the shadow on the wall where the apple hangs will be scarcely half as large as the apple itself. From this you may infer that the earth-circle is round like a ball and not equally near the sun at every point. But where the curved surface lies nearest the sun's path, there will the greatest heat be; and some of the lands that lie continuously under the unbroken rays cannot be inhabited."[43]

Ancient China

Further information: Chinese astronomy

In ancient China, the prevailing belief was that the Earth was flat and square, while the heavens were round,[44] an assumption virtually unquestioned until the introduction of European astronomy in the 17th century.[45][46][47] The English sinologist Cullen emphasizes the point that there was no concept of a round Earth in ancient Chinese astronomy:

Chinese thought on the form of the earth remained almost unchanged from early times until the first contacts with modern science through the medium of Jesuit missionaries in the seventeenth century. While the heavens were variously described as being like an umbrella covering the earth (the Kai Tian theory), or like a sphere surrounding it (the Hun Tian theory), or as being without substance while the heavenly bodies float freely (the Hsüan yeh theory), the earth was at all times flat, although perhaps bulging up slightly.[48]

The model of an egg was often used by Chinese astronomers such as Zhang Heng (78–139 AD) to describe the heavens as spherical:

The heavens are like a hen's egg and as round as a crossbow bullet; the earth is like the yolk of the egg, and lies in the centre.[49]

This analogy with a curved egg led some modern historians, notably Joseph Needham, to conjecture that Chinese astronomers were, after all, aware of the Earth's sphericity. The egg reference, however, was rather meant to clarify the relative position of the flat earth to the heavens:

In a passage of Zhang Heng's cosmogony not translated by Needham, Zhang himself says: "Heaven takes its body from the Yang, so it is round and in motion. Earth takes its body from the Yin, so it is flat and quiescent". The point of the egg analogy is simply to stress that the earth is completely enclosed by heaven, rather than merely covered from above as the Kai Tian describes. Chinese astronomers, many of them brilliant men by any standards, continued to think in flat-earth terms until the seventeenth century; this surprising fact might be the starting-point for a re-examination of the apparent facility with which the idea of a spherical earth found acceptance in fifth-century BC Greece.[50]

Further examples cited by Needham supposed to demonstrate dissenting voices from the ancient Chinese consensus actually refer without exception to the Earth being square, not to it being flat.[51] Accordingly, the 13th-century scholar Li Ye, who argued that the movements of the round heaven would be hindered by a square Earth,[44] did not advocate a spherical Earth, but rather that its edge should be rounded off so as to be circular.[52]

As noted in the book Huainanzi,[53] in the 2nd century BC Chinese astronomers effectively inverted Eratosthenes' calculation of the curvature of the Earth to calculate the height of the sun above the earth. By assuming the earth was flat, they arrived at a distance of 100,000 li (approximately 200,000 km), which is a value far short of the correct distance of 150 million km.

Declining support for the flat Earth

Further information: Spherical Earth and History of geodesy

Ancient Mediterranean

When a ship is at the horizon, its lower part is obscured due to the curvature of the Earth.

Semi-circular shadow of Earth on the Moon during the phases of a lunar eclipse

In The Histories, written in the mid-5th century BC, Herodotus cast doubt on a report of the sun observed shining from the north. He stated that the phenomenon was observed during a circumnavigation of Africa undertaken by Phoenician explorers employed by Egyptian pharaoh Necho II c. 610–595 BC (The Histories, 4.42) who claimed to have had the sun on their right when circumnavigating in a clockwise direction. To modern historians aware of a spherical Earth, these details confirm the truth of the Phoenicians’ report.

After the Greek philosophers Pythagoras, in the 6th century BC, and Parmenides, in the 5th, recognized that the Earth is spherical,[54] the spherical view spread rapidly in the Greek world. Around 330 BC, Aristotle maintained on the basis of physical theory and observational evidence that the Earth was spherical, and reported on an estimate on the circumference.[55] The Earth's circumference was first determined around 240 BC by Eratosthenes.[56] By the second century CE, Ptolemy had derived his maps from a curved globe and developed the system of latitude, longitude, and climes. His Almagest was written in Greek and only translated into Latin in the 11th century from Arabic translations.

The Terrestrial Sphere of Crates of Mallus (c. 150 BC)

In the 2nd century BC, Crates of Mallus devised a terrestrial sphere that divided the Earth into four continents, separated by great rivers or oceans, with people presumed living in each of the four regions.[57] Opposite the oikumene, the inhabited world, were the antipodes, considered unreachable both because of an intervening torrid zone (equator) and the ocean. This took a strong hold on the medieval mind.

Lucretius (1st. c. BC) opposed the concept of a spherical Earth, because he considered that an infinite universe had no center towards which heavy bodies would tend. Thus, he thought the idea of animals walking around topsy-turvy under the Earth was absurd.[58][59] By the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder was in a position to claim that everyone agrees on the spherical shape of Earth,[60] though disputes continued regarding the nature of the antipodes, and how it is possible to keep the ocean in a curved shape. Pliny also considered the possibility of an imperfect sphere, "...shaped like a pinecone."[60]

In late antiquity such widely read encyclopedists as Macrobius (5th century) and Martianus Capella (5th century) discussed the circumference of the sphere of the Earth, its central position in the universe, the difference of the seasons in northern and southern hemispheres, and many other geographical details.[61] In his commentary on Cicero's Dream of Scipio, Macrobius described the Earth as a globe of insignificant size in comparison to the remainder of the cosmos.[61]

Early Christian Church

During the early Church period, the spherical view continued to be widely held, with some notable exceptions.[62]

Lactantius, Christian writer and advisor to the first Christian Roman Emperor, Constantine, ridiculed the notion of the Antipodes, inhabited by people "whose footsteps are higher than their heads". After presenting some arguments he attributes to advocates for a spherical heaven and Earth, he writes:

But if you inquire from those who defend these marvellous fictions, why all things do not fall into that lower part of the heaven, they reply that such is the nature of things, that heavy bodies are borne to the middle, and that they are all joined together towards the middle, as we see spokes in a wheel; but that the bodies that are light, as mist, smoke, and fire, are borne away from the middle, so as to seek the heaven. I am at a loss what to say respecting those who, when they have once erred, consistently persevere in their folly, and defend one vain thing by another.[63]

The influential theologian and philosopher Saint Augustine, one of the four Great Church Fathers of the Western Church, similarly objected to the "fable" of an inhabited Antipodes:

But as to the fable that there are Antipodes, that is to say, men on the opposite side of the earth, where the sun rises when it sets to us, men who walk with their feet opposite ours that is on no ground credible. And, indeed, it is not affirmed that this has been learned by historical knowledge, but by scientific conjecture, on the ground that the earth is suspended within the concavity of the sky, and that it has as much room on the one side of it as on the other: hence they say that the part that is beneath must also be inhabited. But they do not remark that, although it be supposed or scientifically demonstrated that the world is of a round and spherical form, yet it does not follow that the other side of the earth is bare of water; nor even, though it be bare, does it immediately follow that it is peopled. For Scripture, which proves the truth of its historical statements by the accomplishment of its prophecies, gives no false information; and it is too absurd to say, that some men might have taken ship and traversed the whole wide ocean, and crossed from this side of the world to the other, and that thus even the inhabitants of that distant region are descended from that one first man.[64]

The view generally accepted by scholars of Augustine's work is that he shared the common view of his contemporaries that the Earth is spherical,[65] in line with his endorsement of science in De Genesi ad litteram.[66] That view was challenged by noted Augustine scholar Leo Ferrari, who concluded that

he was familiar with the Greek theory of a spherical earth, nevertheless, (following in the footsteps of his fellow North African, Lactantius), he was firmly convinced that the earth was flat, was one of the two biggest bodies in existence and that it lay at the bottom of the universe. Apparently Augustine saw this picture as more useful for scriptural exegesis than the global earth at the centre of an immense universe.[67]

Ferrari's interpretation was questioned by the historian of science, Phillip Nothaft, who considers that in his scriptural commentaries Augustine was not endorsing any particular cosmological model.[68]

Cosmas Indicopleustes' world view – flat earth in a Tabernacle

Diodorus of Tarsus, a leading figure in the School of Antioch and mentor of John Chrysostom, may have argued for a flat Earth; however, Diodorus' opinion on the matter is known only from a later criticism.[69] Chrysostom, one of the four Great Church Fathers of the Eastern Church and Archbishop of Constantinople, explicitly espoused the idea, based on scripture, that the Earth floats miraculously on the water beneath the firmament.[70] Athanasius the Great, Church Father and Patriarch of Alexandria, expressed a similar view in Against the Heathen.[71]

Christian Topography (547) by the Alexandrian monk Cosmas Indicopleustes, who had travelled as far as Sri Lanka and the source of the Blue Nile, is now widely considered the most valuable geographical document of the early medieval age, although it received relatively little attention from contemporaries. In it, the author repeatedly expounds the doctrine that the universe consists of only two places, the Earth below the firmament and heaven above it. Carefully drawing on arguments from scripture, he describes the Earth as a rectangle, 400 day's journey long by 200 wide, surrounded by four oceans and enclosed by four massive walls which support the firmament. The spherical Earth theory is contemptuously dismissed as "pagan".[72][73][74]

Severian, Bishop of Gabala (d. 408), wrote that the Earth is flat and the sun does not pass under it in the night, but "travels through the northern parts as if hidden by a wall".[75] Basil of Caesarea (329–379) argued that the matter was theologically irrelevant.[76]

Early Middle Ages

Early medieval Christian writers in the early Middle Ages felt little urge to assume flatness of the earth, though they had fuzzy impressions of the writings of Ptolemy, Aristotle, and relied more on Pliny.[77]

9th-century Macrobian cosmic diagram showing the sphere of the Earth at the center (globus terrae)

With the end of Roman civilization, Western Europe entered the Middle Ages with great difficulties that affected the continent's intellectual production. Most scientific treatises of classical antiquity (in Greek) were unavailable, leaving only simplified summaries and compilations. Still, many textbooks of the Early Middle Ages supported the sphericity of the Earth. For example: some early medieval manuscripts of Macrobius include maps of the Earth, including the antipodes, zonal maps showing the Ptolemaic climates derived from the concept of a spherical Earth and a diagram showing the Earth (labeled as globus terrae, the sphere of the Earth) at the center of the hierarchically ordered planetary spheres.[78] Further examples of such medieval diagrams can be found in medieval manuscripts of the Dream of Scipio. In the Carolingian era, scholars discussed Macrobius's view of the antipodes. One of them, the Irish monk Dungal, asserted that the tropical gap between our habitable region and the other habitable region to the south was smaller than Macrobius had believed.[79]

12th-century T and O map representing the inhabited world as described by Isidore of Seville in his Etymologiae (chapter 14, de terra et partibus)

Europe's view of the shape of the Earth in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages may be best expressed by the writings of early Christian scholars:

- Boethius (c. 480–524), who also wrote a theological treatise On the Trinity, repeated the Macrobian model of the Earth in the center of a spherical cosmos in his influential, and widely translated, Consolation of Philosophy.[80]

- Bishop Isidore of Seville (560–636) taught in his widely read encyclopedia, the Etymologies diverse views such as that the Earth "resembles a wheel"[81] resembling Anaximander in language and the map that he provided. This was widely interpreted as referring to a flat disc-shaped Earth.[82][83] An illustration from Isidore's De Natura Rerum shows the five zones of the earth as adjacent circles. Some have concluded that he thought the Arctic and Antarctic zones were adjacent to each other.[84] He did not admit the possibility of antipodes, which he took to mean people dwelling on the opposite side of the Earth, considering them legendary[85] and noting that there was no evidence for their existence.[86] Isidore's T and O map, which was seen as representing a small part of a spherical Earth, continued to be used by authors through the Middle Ages, e.g. the 9th-century bishop Rabanus Maurus who compared the habitable part of the northern hemisphere (Aristotle's northern temperate clime) with a wheel. At the same time, Isidore's works also gave the views of sphericity, for example, in chapter 28 of De Natura Rerum, Isidore claims that the sun orbits the earth and illuminates the other side when it is night on this side. See French translation of De Natura Rerum.[87] In his other work Etymologies, there are also affirmations that the sphere of the sky has earth in its center and the sky being equally distant on all sides.[88][89] Other researchers have argued these points as well.[77][90][91] "The work remained unsurpassed until the thirteenth century and was regarded as the summit of all knowledge. It became an essential part of European medieval culture. Soon after the invention of typography it appeared many times in print."[92] However, "The Scholastics - later medieval philosophers, theologians, and scientists - were helped by the Arabic translators and commentaries, but they hardly needed to struggle against a flat-earth legacy from the early middle ages (500-1050). Early medieval writers often had fuzzy and imprecise impressions of both Ptolemy and Aristotle and relied more on Pliny, but they felt (with one exception), little urge to assume flatness."[77]

Isidore's portrayal of the five zones of the earth

- The monk Bede (c. 672–735) wrote in his influential treatise on computus, The Reckoning of Time, that the Earth was round ('not merely circular like a shield [or] spread out like a wheel, but resembl[ing] more a ball'), explaining the unequal length of daylight from "the roundness of the Earth, for not without reason is it called 'the orb of the world' on the pages of Holy Scripture and of ordinary literature. It is, in fact, set like a sphere in the middle of the whole universe." (De temporum ratione, 32). The large number of surviving manuscripts of The Reckoning of Time, copied to meet the Carolingian requirement that all priests should study the computus, indicates that many, if not most, priests were exposed to the idea of the sphericity of the Earth.[93] Ælfric of Eynsham paraphrased Bede into Old English, saying "Now the Earth's roundness and the Sun's orbit constitute the obstacle to the day's being equally long in every land."[94]

- St Vergilius of Salzburg (c. 700–784), in the middle of the 8th century, discussed or taught some geographical or cosmographical ideas that St Boniface found sufficiently objectionable that he complained about them to Pope Zachary. The only surviving record of the incident is contained in Zachary's reply, dated 748, where he wrote:

As for the perverse and sinful doctrine which he (Virgil) against God and his own soul has uttered—if it shall be clearly established that he professes belief in another world and other men existing beneath the earth, or in (another) sun and moon there, thou art to hold a council, deprive him of his sacerdotal rank, and expel him from the Church.[95]

- Some authorities have suggested that the sphericity of the Earth was among the aspects of Vergilius's teachings that Boniface and Zachary considered objectionable.[96][97] Others have considered this unlikely, and take the wording of Zachary's response to indicate at most an objection to belief in the existence of humans living in the antipodes.[98][99][100][101][102] In any case, there is no record of any further action having been taken against Vergilius. He was later appointed bishop of Salzburg, and was canonised in the 13th century.[103]

12th-century depiction of a spherical Earth with the four seasons (book Liber Divinorum Operum by Hildegard of Bingen)

A possible non-literary but graphic indication that people in the Middle Ages believed that the Earth (or perhaps the world) was a sphere is the use of the orb (globus cruciger) in the regalia of many kingdoms and of the Holy Roman Empire. It is attested from the time of the Christian late-Roman emperor Theodosius II (423) throughout the Middle Ages; the Reichsapfel was used in 1191 at the coronation of emperor Henry VI. However the word 'orbis' means 'circle' and there is no record of a globe as a representation of the Earth since ancient times in the west till that of Martin Behaim in 1492. Additionally it could well be a representation of the entire 'world' or cosmos.

A recent study of medieval concepts of the sphericity of the Earth noted that "since the eighth century, no cosmographer worthy of note has called into question the sphericity of the Earth."[104] However, the work of these intellectuals may not have had significant influence on public opinion, and it is difficult to tell what the wider population may have thought of the shape of the Earth, if they considered the question at all.

High and Late Middle Ages

Further information: Spherical Earth § Medieval Europe

Picture from a 1550 edition of On the Sphere of the World, the most influential astronomy textbook of 13th-century Europe

By the 11th century Europe had learned of Islamic astronomy. The Renaissance of the 12th century from about 1070 started an intellectual revitalization of Europe with strong philosophical and scientific roots, and increased interest in natural philosophy.

Illustration of the spherical Earth in a 14th-century copy of L'Image du monde (c. 1246)

Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054) was among the earliest Christian scholars to estimate the circumference of Earth with Eratosthenes' method. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the most important and widely taught theologian of the Middle Ages, believed in a spherical Earth; and he even took for granted his readers also knew the Earth is round.[nb 1] Lectures in the medieval universities commonly advanced evidence in favor of the idea that the Earth was a sphere.[105] Also, "On the Sphere of the World", the most influential astronomy textbook of the 13th century and required reading by students in all Western European universities, described the world as a sphere. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, wrote, "The physicist proves the earth to be round by one means, the astronomer by another: for the latter proves this by means of mathematics, e.g. by the shapes of eclipses, or something of the sort; while the former proves it by means of physics, e.g. by the movement of heavy bodies towards the center, and so forth."[106]

The shape of the Earth was not only discussed in scholarly works written in Latin; it was also treated in works written in vernacular languages or dialects and intended for wider audiences. The Norwegian book Konungs Skuggsjá, from around 1250, states clearly that the Earth is round—and that there is night on the opposite side of the Earth when there is daytime in Norway. The author also discusses the existence of antipodes—and he notes that (if they exist) they see the Sun in the north of the middle of the day, and that they experience seasons opposite those of people in the Northern Hemisphere.

However Tattersall shows that in many vernacular works in 12th- and 13th-century French texts the Earth was considered "round like a table" rather than "round like an apple". "In virtually all the examples quoted...from epics and from non-'historical' romances (that is, works of a less learned character) the actual form of words used suggests strongly a circle rather than a sphere, though notes that even in these works the language is ambiguous.[107]

As late as 1674, Robert Hooke could argue "To one who has been conversant only with illiterate persons, or such as understand not the principles of Astronomy and Geometry,...who can scarce imagine the Earth is globous, but...imagine it to be a round plain covered with the Sky as with a Hemisphere", suggesting that the opinion was not uncommon even then.[108]

Portuguese exploration of Africa and Asia, Columbus's voyage to the Americas (1492) and finally Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the Earth (1519–21) provided the final, practical proofs for the global shape of the Earth.

Islamic world

Further information: Spherical Earth § Medieval Islamic scholars

The Abbasid Caliphate saw a great flowering of astronomy and mathematics in the 9th century CE. in which Muslim scholars translated Ptolemy's work, which become the Almagest, and extended and updated his work based on spherical ideas, and these have generally been respected since. However, after the decline of the Golden Age in the 13th century more traditional views were increasingly heard.[citation needed]

The Quran mentions that the world was "laid out". To this a classic Sunni commentary, the Tafsir al-Kabir (al-Razi) written in the late 12th century says "If it is said: Do the words “And the earth We spread out” indicate that it is flat? We would respond: Yes, because the earth, even though it is round, is an enormous sphere, and each little part of this enormous sphere, when it is looked at, appears to be flat. As that is the case, this will dispel what they mentioned of confusion. The evidence for that is the verse in which Allah says (interpretation of the meaning): “And the mountains as pegs” [an-Naba’ 78:7]. He called them awtaad (pegs) even though these mountains may have large flat surfaces. And the same is true in this case."[109]

A later classic Sunni commentary, the Tafsir al-Jalalayn written in the early 16th century says "As for His words sutihat, ‘laid out flat’, this on a literal reading suggests that the earth is flat, which is the opinion of most of the scholars of the [revealed] Law, and not a sphere as astronomers (ahl al-hay’a) have it, even if this [latter] does not contradict any of the pillars of the Law."[110] Other translations render "made flat" as "spread out".[111]

Ming China

As late as 1595, an early Jesuit missionary to China, Matteo Ricci, recorded that the Chinese say: "The earth is flat and square, and the sky is a round canopy; they did not succeed in conceiving the possibility of the antipodes."[52][112] The universal belief in a flat Earth is confirmed by a contemporary Chinese encyclopedia from 1609 illustrating a flat Earth extending over the horizontal diametral plane of a spherical heaven.[52]

In the 17th century, the idea of a spherical Earth spread in China due to the influence of the Jesuits, who held high positions as astronomers at the imperial court.[113]

Modern period

"Myth of the Flat Earth" in modern historiography

Main article: Myth of the Flat Earth

Martin Behaim's Erdapfel, the oldest surviving terrestrial globe and finished before the news of the discovery of the Americas had reached Europe (1492), demonstrates that knowledge of the round Earth was common on the continent before.

During the 19th century, the Romantic conception of a European "Dark Age" gave much more prominence to Flat Earth beliefs than was historically warranted.

In 1945 the Historical Association listed "Columbus and the Flat Earth Conception" second of twenty in its first-published pamphlet on common errors in history.[114] This belief is even repeated in some widely read textbooks. Previous editions of Thomas Bailey's The American Pageant stated that "The superstitious sailors [of Columbus' crew] ... grew increasingly mutinous...because they were fearful of sailing over the edge of the world"; however, no such historical account is known.[115] Actually, sailors were probably among the first to know of the curvature of Earth from everyday observations, for example seeing how distant ships disappear from view from bottom up, sailing over the curvature of the sea.

Some historians consider that the early advocates who projected flat Earth upon Christians of the Middle Ages were highly influential (19th-century view typified by Andrew Dickson White); current historians (late 20th-century view typified by historian and religious studies scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell)[116] have asserted that White's and other writings projecting flat Earth belief upon Christians are inaccurate, citing centuries of theological writings, and suggested the motivations for the promotion of such inaccuracies.

According to Russell,[117] the common misconception that people before the age of exploration believed that Earth was flat entered the popular imagination after Washington Irving's publication of A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1828.[118] Although some of the arguments attributed by Irving to Columbus's opponents had been recorded not long after the latter's death, here are only hints that any argued that the Earth was flat, in the argument that the ocean might be infinite in extent, repeated by later historians.[119] Other arguments were based on the impossibility of the antipodes, the vast size of the Earth, the impossibility of going from one hemisphere to the others, and other arguments based on the sphericity of the Earth.[120] Modern historians have dismissed the claim that they maintained the earth was flat as a fabrication of Irving's.[121][122][123][124]

The only denial published at the time came from Zacharia Lilio, a canon of the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome in 1496. In a section entitled "That the earth is not round" he argues that "when they assert that the earth is round, Ptolemy and Pliny do not add to the evidence, collected on the spot, they simply make a conjecture based solely on reasoning".[125] Copernicus, writing only twenty years after Columbus in 1514, dismisses the idea of a flat Earth in two sentences and cites supporters only from antiquity, though he expends more effort on showing that other current ideas were fallacious and demonstrating the sphericity of the earth.[126] In reality, the issue in the 1490s was not the shape but the size of the Earth, as well as the position of the east coast of Asia.

Modern Flat-Earthers

Flat Earth map drawn by Orlando Ferguson in 1893. The map contains several references to biblical passages as well as various jabs at the "Globe Theory".

In the modern era, belief in a flat Earth has been expressed by isolated individuals and groups, but no scientists of note. English writer Samuel Rowbotham (1816–1885), writing under the pseudonym "Parallax," produced a pamphlet called Zetetic Astronomy in 1849 arguing for a flat Earth and published results of many experiments that tested the curvatures of water over a long drainage ditch, followed by another called The inconsistency of Modern Astronomy and its Opposition to the Scripture. One of his supporters, John Hampden, lost a bet to Alfred Russel Wallace in the famous Bedford Level Experiment, which attempted to prove it. In 1877 Hampden produced a book called "A New Manual of Biblical Cosmography".[127] Rowbotham also produced studies that purported to show that the effects of ships disappearing below the horizon could be explained by the laws of perspective in relation to the human eye.[128]

In 1883 he founded Zetetic Societies in England and New York, to which he shipped a thousand copies of Zetetic Astronomy. Challenges were issued in the New York Daily Graphic offering $10,000 to charity to anyone proving the Earth revolved on an axis.

William Carpenter, a printer originally from Greenwich, England, was a supporter of Rowbotham and published Theoretical Astronomy Examined and Exposed – Proving the Earth not a Globe in eight parts from 1864 under the name Common Sense.[129] He later emigrated to Baltimore where he published A hundred proofs the Earth is not a Globe in 1885.[130] He argues that:

- "There are rivers that flow for hundreds of miles towards the level of the sea without falling more than a few feet — notably, the Nile, which, in a thousand miles, falls but a foot. A level expanse of this extent is quite incompatible with the idea of the Earth's convexity. It is, therefore, a reasonable proof that Earth is not a globe."

- "If the Earth were a globe, a small model globe would be the very best — because the truest — thing for the navigator to take to sea with him. But such a thing as that is not known: with such a toy as a guide, the mariner would wreck his ship, of a certainty!, This is a proof that Earth is not a globe."

John Jasper, the black ex-slave preacher said to have preached to more people than any Southern clergyman of his generation, echoed his friend Carpenter's sentiments in his most famous sermon "Der Sun do move and the Earth Am Square", preached over 250 times always by invitation.[131]

In Brockport, N.Y, in 1887, M.C. Flanders argued the case of a flat Earth for three nights against two scientific gentlemen defending sphericity. Five townsmen chosen as judges voted unanimously for a flat Earth at the end. The case was reported in the Brockport Democrat.[132]

"Professor" Joseph W. Holden of Maine, a former justice of the peace, gave numerous lectures in New England and lectured on flat Earth theory at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His fame stretched to North Carolina where the Statesville Semi-weekly Landmark recorded at his death in 1900: 'We hold to the doctrine that the earth is flat ourselves and we regret exceedingly to learn that one of our members is dead'.[133]

After Rowbotham's death, Lady Elizabeth Blount created the Universal Zetetic Society in 1893 in England and created a journal called Earth not a Globe Review, which sold for twopence, as well as one called Earth, which only lasted from 1901 to 1904. She held that the Bible was the unquestionable authority on the natural world and argued that one could not be a Christian and believe the Earth is a globe. Well-known members included E. W. Bullinger of the Trinitarian Bible Society, Edward Haughton, senior moderator in natural science in Trinity College, Dublin and an archbishop. She repeated Rowbotham's experiments, generating some interesting counter-experiments, but interest declined after the First World War.[133] The movement gave rise to several books that argued for a flat, stationary earth, including Terra Firma by David Wardlaw Scott.[134]

In 1898, during his solo circumnavigation of the world, Joshua Slocum encountered a group of flat-Earthers in Durban. Three Boers, one of them a clergyman, presented Slocum with a pamphlet in which they set out to prove that the world was flat. Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal Republic, advanced the same view: "You don't mean round the world, it is impossible! You mean in the world. Impossible!"[135]

Wilbur Glenn Voliva, who in 1906 took over the Christian Catholic Church, a Pentecostal sect that established a utopian community at Zion, Illinois, preached flat Earth doctrine from 1915 onwards and used a photograph of a twelve-mile stretch of the shoreline at Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin taken three feet above the waterline to prove his point. When the airship Italia disappeared on an expedition to the North Pole in 1928 he warned the world's press that it had sailed over the edge of the world. He offered a $5,000 award for proving the Earth is not flat, under his own conditions.[136] Teaching a globular Earth was banned in the Zion schools and the message was transmitted on his WCBD radio station.[133]

Mohammed Yusuf, founder of the Nigerian militant Islamist group Boko Haram, stated his belief in a flat Earth.[137]

Flat Earth Society

Main article: Modern Flat Earth societies

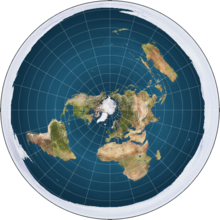

azimuthal equidistant projections of the sphere like this one have also been co-opted as images of the flat Earth model depicting Antarctica as an ice wall[138][139] surrounding a disk-shaped Earth.

In 1956, Samuel Shenton set up the International Flat Earth Research Society (IFERS), better known as the Flat Earth Society from Dover, UK, as a direct descendant of the Universal Zetetic Society. This was just before the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik; he responded, "Would sailing round the Isle of Wight prove that it were spherical? It is just the same for those satellites."

His primary aim was to reach children before they were convinced about a spherical Earth. Despite plenty of publicity, the space race eroded Shenton's support in Britain until 1967 when he started to become famous due to the Apollo program. His postbag was full but his health suffered as his operation remained essentially a one-man show until he died in 1971.[133]

In 1972 Shenton's role was taken over by Charles K. Johnson, a correspondent from California, USA. He incorporated the IFERS and steadily built up the membership to about 3,000. He spent years examining the studies of flat and round Earth theories and proposed evidence of a conspiracy against flat-Earth: "The idea of a spinning globe is only a conspiracy of error that Moses, Columbus, and FDR all fought..." His article was published in the magazine Science Digest, 1980. It goes on to state, "If it is a sphere, the surface of a large body of water must be curved. The Johnsons have checked the surfaces of Lake Tahoe and the Salton Sea without detecting any curvature."[140]

The Society declined in the 1990s following a fire at its headquarters in California and the death of Johnson in 2001.[141] It was revived as a website in 2004 by Daniel Shenton (no relation to Samuel Shenton). He believes that no one has provided proof that the world is not flat.[142]

Cultural references

The notion of a flat Earth survives in a wide range of contexts. Indirect references to the theory include the widely used idiom the four corners of the earth. The term "flat-Earther" is often used in a derogatory sense to mean anyone who holds ridiculously antiquated views.

The first use of the term flat-earther recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is in 1934 in Punch: "Without being a bigoted flat-earther, he [sc. Mercator] perceived the nuisance..of fiddling about with globes..in order to discover the South Seas."[143] The term flat-earth-man was recorded in 1908: "Fewer votes than one would have thought possible for any human candidate, were he even a flat-earth-man."[144]

An early mention in literature was Ludvig Holberg's comedy Erasmus Montanus (1723). Erasmus Montanus meets considerable opposition when he claims the Earth is round, since all the peasants believe it is flat. He is not allowed to marry his fiancée until he cries, "The earth is flat as a pancake." In Rudyard Kipling's The Village that Voted the Earth was Flat, the protagonists spread the rumor that a Parish Council meeting had voted in favor of a flat Earth.

Scientific satire

In a satirical piece published 1996, Albert A. Bartlett uses arithmetic to show that sustainable growth on Earth is impossible in a spherical Earth since its resources are necessarily finite. He explains that only a model of a flat Earth, stretching infinitely in the two horizontal dimensions and also in the vertical downward direction, would be able to accommodate the needs of a permanently growing population.

Referring to Julian Simon's book The Ultimate Resource, Bartlett suggests "So, let us think of the “We’re going to grow the limits!” people as the “New Flat Earth Society.”"[145] The satiric nature of the piece is also made clear by a comparison to Bartlett's other publications, which mainly advocate the necessity of curbing population growth.[146]

http://www.theflatearthsociety.org/cms/

Are Flat-Earthers Being Serious?

by Natalie Wolchover | October 26, 2012 10:29am ET

A Flat Earth model depicting Antarctica as an ice wall surrounding a disc-shaped Earth.

Credit: Creative Commons 1.0 Generic | Trekky0623

Members of the Flat Earth Society claim to believe the Earth is flat. Walking around on the planet's surface, it looks and feels flat, so they deem all evidence to the contrary, such as satellite photos of Earth as a sphere, to be fabrications of a "round Earth conspiracy" orchestrated by NASA and other government agencies.

The belief that the Earth is flat has been described as the ultimate conspiracy theory. According to the Flat Earth Society's leadership, its ranks have grown by 200 people (mostly Americans and Britons) per year since 2009. Judging by the exhaustive effort flat-earthers have invested in fleshing out the theory on their website, as well as the staunch defenses of their views they offer in media interviews and on Twitter, it would seem that these people genuinely believe the Earth is flat.

But in the 21st century, can they be serious? And if so, how is this psychologically possible?

Through a flat-earther's eyes

First, a brief tour of the worldview of a flat-earther: While writing off buckets of concrete evidence that Earth is spherical, they readily accept a laundry list of propositions that some would call ludicrous. The leading flat-earther theory holds that Earth is a disc with the Arctic Circle in the center and Antarctica, a 150-foot-tall wall of ice, around the rim. NASA employees, they say, guard this ice wall to prevent people from climbing over and falling off the disc. Earth's day and night cycle is explained by positing that the sun and moon are spheres measuring 32 miles (51 kilometers) that move in circles 3,000 miles (4,828 km) above the plane of the Earth. (Stars, they say, move in a plane 3,100 miles up.) Like spotlights, these celestial spheres illuminate different portions of the planet in a 24-hour cycle. Flat-earthers believe there must also be an invisible "antimoon" that obscures the moon during lunar eclipses.

Furthermore, Earth's gravity is an illusion, they say. Objects do not accelerate downward; instead, the disc of Earth accelerates upward at 32 feet per second squared (9.8 meters per second squared), driven up by a mysterious force called dark energy. Currently, there is disagreement among flat-earthers about whether or not Einstein's theory of relativity permits Earth to accelerate upward indefinitely without the planet eventually surpassing the speed of light. (Einstein's laws apparently still hold in this alternate version of reality.)

As for what lies underneath the disc of Earth, this is unknown, but most flat-earthers believe it is composed of "rocks." [Religion and Science: 6 Visions of Earth's Core]

Then, there's the conspiracy theory: Flat-earthers believe photos of the globe are photoshopped; GPS devices are rigged to make airplane pilots think they are flying in straight lines around a sphere when they are actually flying in circles above a disc. The motive for world governments' concealment of the true shape of the Earth has not been ascertained, but flat-earthers believe it is probably financial. "In a nutshell, it would logically cost much less to fake a space program than to actually have one, so those in on the Conspiracy profit from the funding NASA and other space agencies receive from the government," the flat-earther website's FAQ page explains.

It's no joke

The theory follows from a mode of thought called the "Zetetic Method," an alternative to the scientific method, developed by a 19th-century flat-earther, in which sensory observations reign supreme. "Broadly, the method places a lot of emphasis on reconciling empiricism and rationalism, and making logical deductions based on empirical data," Flat Earth Society vice president Michael Wilmore, an Irishman, told Life's Little Mysteries. In Zetetic astronomy, the perception that Earth is flat leads to the deduction that it must actually be flat; the antimoon, NASA conspiracy and all the rest of it are just rationalizations for how that might work in practice.

Those details make the flat-earthers' theory so elaborately absurd it sounds like a joke, but many of its supporters genuinely consider it a more plausible model of astronomy than the one found in textbooks. In short, they aren't kidding. [50 Amazing Facts About Planet Earth]

"The question of belief and sincerity is one that comes up a lot," Wilmore said. "If I had to guess, I would probably say that at least some of our members see the Flat Earth Society and Flat Earth Theory as a kind of epistemological exercise, whether as a critique of the scientific method or as a kind of 'solipsism for beginners.' There are also probably some who thought the certificate would be kind of funny to have on their wall. That being said, I know many members personally, and I am fully convinced of their belief."

Wilmore counts himself among the true believers. "My own convictions are a result of philosophical introspection and a considerable body of data that I have personally observed, and which I am still compiling,” he said.

Strangely, Wilmore and the society's president, a 35-year-old Virginia-born Londoner named Daniel Shenton, both think the evidence for global warming is strong, despite much of this evidence coming from satellite data gathered by NASA, the kingpin of the "round Earth conspiracy." They also accept evolution and most other mainstream tenets of science.

Conspiracy theory psychology

As inconceivable as their belief system seems, it doesn't really surprise experts. Karen Douglas, a psychologist at the University of Kent in the United Kingdom who studies the psychology of conspiracy theories, says flat-earthers' beliefs cohere with those of other conspiracy theorists she has studied.

"It seems to me that these people do generally believe that the Earth is flat. I'm not seeing anything that sounds as if they're just putting that idea out there for any other reason," Douglas told Life's Little Mysteries.

She said all conspiracy theories share a basic thrust: They present an alternative theory about an important issue or event, and construct an (often) vague explanation for why someone is covering up that "true" version of events. "One of the major points of appeal is that they explain a big event but often without going into details," she said. "A lot of the power lies in the fact that they are vague."

The self-assured way in which conspiracy theorists stick to their story imbues that story with special appeal. After all, flat-earthers are more adamant that the Earth is flat than most people are that the Earth is round (probably because the rest of us feel we have nothing to prove). "If you're faced with a minority viewpoint that is put forth in an intelligent, seemingly well-informed way, and when the proponents don't deviate from these strong opinions they have, they can be very influential. We call that minority influence," Douglas said.

In a recent study, Eric Oliver and Tom Wood, political scientists at the University of Chicago, found that about half of Americans endorse at least one conspiracy theory, from the notion that 9/11 was an inside job to the JFK conspiracy. "Many people are willing to believe many ideas that are directly in contradiction to a dominant cultural narrative," Oliver told Life's Little Mysteries. He says conspiratorial belief stems from a human tendency to perceive unseen forces at work, known as magical thinking. [Top Ten Unexplained Phenomena]

However, flat-earthers don't fit entirely snugly in this general picture. Most conspiracy theorists adopt many fringe theories, even ones that contradict each other. Meanwhile, flat-earthers' only hang-up is the shape of the Earth. "If they were like other conspiracy theorists, they should be exhibiting a tendency toward a lot of magical thinking, such as believing in UFOs, ESP, ghosts, the Devil, or other unseen, intentional forces," Oliver wrote in an email. "It doesn't sound like they do, which makes them very anomalous relative to most Americans who believe in conspiracy theories."

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover or Life's Little Mysteries @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Has the “Flat Earth Theory” Found A New Audience?

It’s the last thing that most would ever think they would have to make a case for in the modern world: why the Earth is indeed a globe, and not a flat plane covered with topographical features like mountains and valleys, drifting along like an island in space.

Strange as it may sound, this was precisely the kind of argument I recently found myself having to address, in response to a discussion that took place on an online radio show which apparently brought the so-called “flat earth theory” back into question… at least in the minds of some.

The host in question, Rob Skiba, had been interviewing a fellow named Mark Sargent, a man with a background in graphics and CGI, in which the two men had a lengthy discussion about whether evidence supported a cover-up to withhold information about Earth’s true shape from the public (to his credit, and I want to be clear about this, Skiba made it known at the outset that he doesn’t believe in the idea that our planet is literally flat, though admittedly, a strong sense of favor toward the idea seemed to remain present throughout the discussion).

One of my readers contacted me about the interview, and asked if I would consider listening to what the men had to say, which I did. Among the kinds of points addressed were the fact that NASA and other space agencies have continually released CGI representations of Earth over the years, and that only one supposed “photo” released by NASA actually exists, purporting to show our round globe. Furthermore, anecdotal claims have arisen over the years about visitors to Antarctica being driven away “at gunpoint.” Paired with the fact that world organizations such as the United Nations feature flat earth symbolism in their logos, all of these points are believed to be “evidence” that our world is, indeed, a flat circular plane contained under a dome… a reality which elitists are working hard to hide from the public.

The fact that such “flat earth theories” have lingered into the present day is really nothing new; consider websites like that of The Flat Earth Society, which just last year announced its intention to expand its social media presence. “To kick this off,” one flat-earther had written at their site, “we’ll be running a celebratory campaign that showcases our supporters all over the Disk… We will be regramming the photos across our social media network so people can see our supporters all across the world.”

One must ask themselves, how could someone really believe that the Earth is flat, despite what are now centuries-old determinations first made by the likes of Eratosthenes, who as far back as 235 BC was able to prove its roundness using mathematic calculations?

Let’s remember that Eratosthenes was able make such determinations about our Earth’s shape based on differences in the length of shadows cast by objects in two separate locations, one being the ancient Syene (now Aswan), and the other at Alexandria, on the day of the Summer Solstice. This story was illustrated famously by Carl Sagan in an episode of the classic Cosmos television series, as seen here:

Despite being able to use mathematics to determine the Earth’s roundness as far back as 235 BC, the pseudoscientific interpretation of various data in modern times has nonetheless contributed to the continuation of “flat earth” theories. For instance, as discussed during Skiba’s radio program on the subject, many have taken issue with the fact that images that purportedly feature our planet are “digital composites,” which some interpret to mean that they are purely fabrications using CGI technologies.

In response to questions my reader had asked about such things, I recommended a page where several photos of Earth taken in recent years could be viewed, all of which are composites that were assembled from photos using satellite imaging technologies:

http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view.php?id=79787

To give an idea of the language that I think has led to misunderstandings of what a “composite” or “synthesized” image actually is, I’ll include one of the captions from the images, which reads as follows:

“Over a period of six orbits on on February 3, 2012, the recently launched Suomi NPP satellite provided the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) instrument enough time to gather the pixels for this synthesized view of Earth showing North Africa and southwestern Europe.”

Let’s look at precisely what “composite” or “synthesized view of Earth” actually means. What we’re talking about here are sets of images that cover large portions of the Earth, and at considerably high resolutions. Experts will take the entire set of images, and then collect and combine the most visually useful portions from specific frames, and produce new composites that help reduce the presence of things like cloud formations that might obscure visibility of geographic features below. Using this technique, famous renderings such as the various incarnations known as “The Blue Marble” have been achieved, and while assembled from more than one image, they are by no means complete CGI fabrications. Again, my impression is that during the “flat earth” interview in question, images like those linked above were interpreted as being entirely digital renderings, which simply isn’t the case. As far as their source, most of the images in the link above were obtained either via the Suomi satellite, or the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard the Terra research satellite.

Antarctica

Moving along to address other points, let’s head further south, and around to the idea that Antarctica holds the key to unraveling the “flat earth” secret. Specifically, I’m interested in these anecdotal reports that suggest how those who have attempted to go there and investigate have “been driven away at gunpoint.”

Sure, Antarctica seems like the last place many would actually choose to visit, and hence the place no doubt maintains an air of mystique about it. This is especially the case when considering all the rumors associated with “dangers” Admiral Richard E. Byrd purportedly encountered there during the ill-fated Antarctic expedition called Operation Highjump, which some have associated with post-war Nazi conspiracies.

The truth about our coldest continent, however, and the visitors it receives, is a very different story. It was estimated in January that some 37,000 tourists will visit Antarctica this year alone (though around 10,000 won’t actually set foot on shore), as discussed in a BBC article earlier this year that examined such things as the environmental impact of such heavy visitation. Additionally, as many as 5,000 people actually may reside there annually, at any of the various research stations located on the continent. In summary, if people visiting there were being “turned away at gunpoint,” it seems that at least some of the 37,000 or so planning on visiting would have said something about this.

Conspiratorial scenarios such as those addressed here help show us one thing: that those who become proponents of ideas such as a “flat earth theory” have convinced themselves that their proof lies not in tangible facts or data, but within the evidences of a perceived conspiracy to conceal the “real truth” from the rest of us… which is nonsense. This is not “proof” at all, and such ideas have little — if any — reliance on real facts. On the other hand, a broad history of testable, repeatable data spanning more than 2,000 years proves for us, without a doubt, that our Earth is indeed a globe; just like our moon which we can see clearly on most nights, and several planets further away that are very much like our own, made visible with as little as a telescope one can purchase online.

In conclusion, I would like to observe here that, generally, the attitude conveyed by many within the modern skeptical movement toward those who propose such “fringe” ideas tends to be one not only of dismissal, but also ridicule. In fairness, I think I can understand their frustration, especially in this case; it is indeed troubling that ideas such as this might find an audience today, despite centuries of scientific work aimed at properly educating the public at large, with hope of preventing such falsehoods from finding their way into modern belief systems.

Years ago, when Carl Sagan was met with pseudoscientific claims like these, of course he would differ just as strongly; but he would also rely on an evidence-based approach to refuting such ideas that was both educational, and conducive to dialogue on the issues, rather than being purely confrontational. He was a gentleman, in other words.

Somewhere along the way, we seem to have lost the idea that discourse in relation to such ideas can occur in a civil fashion, and without having to rely on heavy cynicism and ad hominem attacks to get our points across. Therefore, here I hope the discussion presented has been, perhaps in the most literal sense, “civil discourse”, but also that the point has been made effectively too: any remaining advocacy of a “flat earth theory”, however absurd it may be, will hopefully be viewed with a bit more scrutiny by any proponents reading about it here. I think it is fair to call the idea absurd, as most would agree: but by the same token, having such an absurd debate is important, in my opinion, because it outlines how easily people can fall into fallacious thinking, despite the vast amounts of knowledge at our disposal in the present day.

I maintain that it’s alright to “ask questions”, and yes, I also think that doing so is at the very heart of good skepticism. But what also must be considered is whether the questions we’re asking send us along the best lines of thought that we could be following, and whether their outcome will present us with logical conclusions, or merely opinions based on circumstance, in the absence of any real facts.

This fundamental differentiation is the key, I think, and mastering this skill may be the best way to know what it truly means to be asking the right questions.

Comments

Post a Comment