PESTILENCES

35 of the Most Dangerous Viruses and Bacteria's in the World Today

The Black Plague, Marburg, Ebola, Influenza, Enterovirus virus may all sound terrifying, but it's not the most dangerous virus in the world. It isn't HIV either. Here is a list of the most dangerous viruses and Bacteria’s on the Planet Earth.

1. Marburg Virus The most dangerous virus is the Marburg virus. It is named after a small and idyllic town on the river Lahn - but that has nothing to do with the disease itself. The Marburg virus is a hemorrhagic fever virus. As with Ebola, the Marburg virus causes convulsions and bleeding of mucous membranes, skin and organs. It has a fatality rate of 90 percent. The Marburg virus causes a rare, but severe hemorrhagic fever that has a fatality rate of 88%. It was first identified in 1967 when outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever cropped up simultaneously in Marburg, where the disease got its name, Frankfurt in Germany and Belgrade, Serbia.

Marburg and Ebola came from the Filoviridae family of viruses. They both have the capacity to cause dramatic outbreaks with the greatest fatality rates. It is transmitted to humans from fruit bats and spreads to humans through direct contact with the blood, secretions and other bodily fluids of infected humans. No anti-viral treatment or vaccine exists against the Marburg virus. In 1967, a group of lab workers in Germany (Marburg and Frankfurt) and Serbia (then Yugoslavia) contracted a new type of hemorrhagic fever from some virus-carrying African green monkeys that had been imported for research and development of polio vaccines. The Marburg virus is also BSL-4, and Marburg hemorrhagic fever has a 23 to 90 percent fatality rate. Spread through close human-to-human contact, symptoms start with a headache, fever, and a rash on the trunk, and progress to multiple organ failure and massive internal bleeding.

There is no cure, and the latest cases were reported out of Uganda at the end of 2012. An American tourist who had explored a Ugandan cave full of fruit bats known to be reservoirs of the virus contracted it and survived in 2008. (But not before bringing his sick self back to the U.S.)

2014 A man has died in Uganda’s capital after an outbreak of Marburg, a highly infectious haemorrhagic fever similar to Ebola, authorities said on Sunday, adding that a total of 80 people who came into contact with him had been put under quarantine.

2. Ebola Virus There are five strains of the Ebola virus, each named after countries and regions in Africa: Zaire, Sudan, Tai Forest, Bundibugyo and Reston. The Zaire Ebola virus is the deadliest, with a mortality rate of 90 percent. It is the strain currently spreading through Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, and beyond. Scientists say flying foxes probably brought the Zaire Ebola virus into cities.

Typically less than 100 lives a year. UPDATE: A severe Ebola outbreak was detected in West Africa in March 2014. The number of deaths in this latest outbreak has outnumbered all other known cases from previous outbreaks combined. The World Health Organization is reporting nearly 2,000 deaths in this latest outbreak.

Once a person is infected with the virus, the disease has an incubation period of 2-21 days; however, some infected persons are asymptomatic. Initial symptoms are sudden malaise, headache, and muscle pain, progressing to high fever, vomiting, severe hemorrhaging (internally and out of the eyes and mouth) and in 50%-90% of patients, death, usually within days. The likelihood of death is governed by the virulence of the particular Ebola strain involved. Ebola virus is transmitted in body fluids and secretions; there is no evidence of transmission by casual contact. There is no vaccine and no cure.

Its melodic moniker may roll off the tongue, but if you contract the virus (above), that's not the only thing that will roll off one of your body parts (a disturbing amount of blood coming out of your eyes, for instance). Four of the five known Ebola viral strains cause Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), which has killed thousands of people in sub-Saharan African nations since its discovery in 1976.

The deadly virus is named after the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo where it was first reported, and is classified as a CDC Biosafety Level 4, a.k.a. BSL-4, making it one of the most dangerous pathogens on the planet. It is thought to spread through close contact with bodily secretions. EHF has a 50 to 90 percent mortality rate, with a rapid onset of symptoms that start with a headache and sore throat and progress to major internal and external bleeding and multiple organ failure. There’s no known cure, and the most recent cases were reported at the end of 2012 in Uganda.

2014 Ebola continues to rage out of control in West Africa. It is being reported that Sierra Leone just added 121 new Ebola deaths to the overall death toll in a single day. If Ebola continues to spread at an exponential rate, it is inevitable that more people will leave West Africa with the virus and take it to other parts of the globe. In fact, it was being reported on Monday Oct 6 2014 that researchers have concluded that there is “a 50 percent chance” that Ebola could reach the UK by

They claim there is a 50 percent chance the virus could hit Britain by that date and a 75 percent chance the it could be imported to France, as the deadliest outbreak in history spreads across the world. Currently, there is no cure for the disease, which has claimed more than 3,400 lives since March and has a 90 percent fatality rate.

3. The Hantavirus describes several types of viruses. It is named after a river where American soldiers were first thought to have been infected with the Hantavirus, during the Korean War in 1950. Symptoms include lung disease, fever and kidney failure.

70,000 Deaths a Year

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) is a deadly disease transmitted by infected rodents through urine, droppings, or saliva. Humans can contract the disease when they breathe in aerosolized virus. HPS was first recognized in 1993 and has since been identified throughout the United States. Although rare, HPS is potentially deadly. Rodent control in and around the home remains the primary strategy for preventing hantavirus infection. Also known as House Mouse Flu. The symptoms, which are very similar to HFRS, include tachycardia and tachypnea. Such conditions can lead to a cardiopulmonary phase, where cardiovascular shock can occur, and hospitalization of the patient is required.

There are many strains of hantavirus floating around (yep, it’s airborne) in the wake of rodents that carry the virus. Different strains, carried by different rodent species, are known to cause different types of illnesses in humans, most notably hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS)—first discovered during the Korean War—and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), which reared its ugly head with a 1993 outbreak in the Southwestern United States. Severe HFRS causes acute kidney failure, while HPS gets you by filling your lungs with fluid (edema). HFRS has a mortality rate of 1 to 15 percent, while HPS is 38 percent. The U.S. saw its most recent outbreak of hantavirus—of the HPS variety—at Yosemite National Park in late 2012.

4. Avian Influenza Bird Flu The various strains of bird flu regularly cause panic - which is perhaps justified because the mortality rate is 70 percent. But in fact the risk of contracting the H5N1 strain - one of the best known - is quite low. You can only be infected through direct contact with poultry. It is said this explains why most cases appear in Asia, where people often live close to chickens.

This form of the flu is common among birds (usually poultry) and infects humans through contact with secretions of an infected bird.

Although rare, those infected have a high incidence of death. Symptoms are like those of the more common human form of influenza.

Bird flu (H5N1) has receded from international headlines for the moment, as few human cases of the deadly virus have been reported this year. But when Dutch researchers recently created an even more transmissible strain of the virus in a laboratory for research purposes, they stirred grave concerns about what would happen if it escaped into the outside world. “Part of what makes H5N1 so deadly is that most people lack an immunity to it,” explains Marc Lipsitch, a professor of epidemiology at Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) who studies the spread of infectious diseases. “If you make a strain that’s highly transmissible between humans, as the Dutch team did, it could be disastrous if it ever escaped the lab.”

H5N1 first made global news in early 1997 after claiming two dozen victims in Hong Kong. The virus normally occurs only in wild birds and farm-raised fowl, but in those isolated early cases, it made the leap from birds to humans. It then swept unimpeded through the bodies of its initial human victims, causing massive hemorrhages in the lungs and death in a matter of days. Fortunately, during the past 15 years, the virus has claimed only 400 victims worldwide—although the strain can jump species, it hasn’t had the ability to move easily from human to human, a critical limit to its spread.

That’s no longer the case, however. In late 2011, the Dutch researchers announced the creation of an H5N1 virus transmissible through the air between ferrets (the best animal model for studying the impact of disease on humans). The news caused a storm of controversy in the popular press and heated debate among scientists over the ethics of the work. For Lipsitch and many others, the creation of the new strain was cause for alarm. “H5N1 influenza is already one of the most deadly viruses in existence,” he says. “If you make [the virus] transmissible [between humans], you have to be very concerned about what the resulting strain could do.”

To put this danger in context, the 1918 “Spanish” flu—one of the most deadly influenza epidemics on record—killed between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide, or roughly 3 to 6 percent of those infected. The more lethal SARS virus (see “The SARS Scare,” March-April 2007, page 47) killed almost 10 percent of infected patients during a 2003 outbreak that reached 25 countries worldwide. H5N1 is much more dangerous, killing almost 60 percent of those who contract the illness.

If a transmissible strain of H5N1 escapes the lab, says Lipsitch, it could spark a global health catastrophe. “It could infect millions of people in the United States, and very likely more than a billion people globally, like most successful flu strains do,” he says. “This might be one of the worst viruses—perhaps the worst virus—in existence right now because it has both transmissibility and high virulence.”

Ironically, this is why Ron Fouchier, the Dutch virologist whose lab created the new H5N1 strain, argues that studying it in more depth is crucial. If the virus can be made transmissible in the lab, he reasons, it can also occur in nature—and researchers should have an opportunity to understand as much as possible about the strain before that happens.

Lipsitch, who directs the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at HSPH, thinks the risks far outweigh the rewards. Even in labs with the most stringent safety requirements, such as enclosed rubber “space suits” to isolate researchers, accidents do happen. A single unprotected breath could infect a researcher, who might unknowingly spread the virus beyond the confines of the lab.

In an effort to avoid this scenario, Lipsitch has been pushing for changes in research policy in the United States and abroad. (A yearlong, voluntary global ban on H5N1 research was lifted in many countries in January, and new rules governing such research in the United States were expected in February.) Lipsitch says that none of the current research proposals he has seen “would significantly improve our preparational response to a national pandemic of H5N1. The small risk of a very large public health disaster…is not worth taking [for] scientific knowledge without an immediate public health application.” His recent op-eds in scientific journals and the popular press have stressed the importance of regulating the transmissible strain and limiting work with the virus to only a handful of qualified labs. In addition, he argues, only technicians who have the right training and experience—and have been inoculated against the virus—should be allowed to handle it.

These are simple limitations that could drastically reduce the danger of the virus spreading, he asserts, yet they’re still not popular with some researchers. He acknowledges that limiting research is an unusual practice scientifically but argues, “These are unusual circumstances.”

Lipsitch thinks a great deal of useful research can still be done on the non-transmissible strain of the virus, which would provide valuable data without the risk of accidental release. In the meantime, he hopes to make more stringent H5N1 policies a priority for U.S. and foreign laboratories. Although it’s not a perfect solution, he says, it’s far better than a nightmare scenario.

5. Lassa Virus A nurse in Nigeria was the first person to be infected with the Lassa virus. The virus is transmitted by rodents. Cases can be endemic - which means the virus occurs in a specific region, such as in western Africa, and can reoccur there at any time. Scientists assume that 15 percent of rodents in western Africa carry the virus.

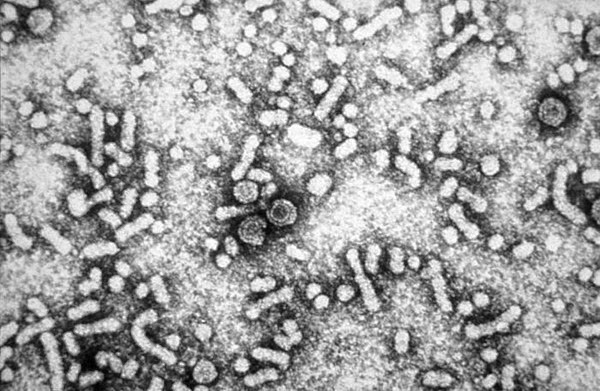

The Marburg virus under a microscope

This BSL-4 virus gives us yet another reason to avoid rodents. Lassa is carried by a species of rat in West Africa called Mastomys. It’s airborne…at least when you’re hanging around the rat's fecal matter. Humans, however, can only spread it through direct contact with bodily secretions. Lassa fever, which has a 15 to 20 percent mortality rate, causes about 5000 deaths a year in West Africa, particularly in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

It starts with a fever and some retrosternal pain (behind the chest) and can progress to facial swelling, encephalitis, mucosal bleeding and deafness. Fortunately, researchers and medical professionals have found some success in treating Lassa fever with an antiviral drug in the early stages of the disease.

6. The Junin Virus is associated with Argentine hemorrhagic fever. People infected with the virus suffer from tissue inflammation, sepsis and skin bleeding. The problem is that the symptoms can appear to be so common that the disease is rarely detected or identified in the first instance.

A member of the genus Arenavirus, Junin virus characteristically causes Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF). AHF leads to major alterations within the vascular, neurological and immune systems and has a mortality rate of between 20 and 30%. Symptoms of the disease are conjunctivitis, purpura, petechia and occasional sepsis. The symptoms of the disease are relatively indistinct and may therefore be mistaken for a different condition.

Since the discovery of the Junin virus in 1958, the geographical distribution of the pathogen, although still confined to Argentina, has risen. At the time of discovery, Junin virus was confined to an area of around 15,000 km². At the beginning of 2000, the distribution had risen to around 150,000 km². The natural hosts of Junin virus are rodents, particularly Mus musculus, Calomys spp. and Akodon azarae.

Direct rodent to human transmission only transpires when contact is made with excrement of an infected rodent. This commonly occurs via ingestion of contaminated food or water, inhalation of particles within urine or via direct contact of broken skin with rodent excrement.

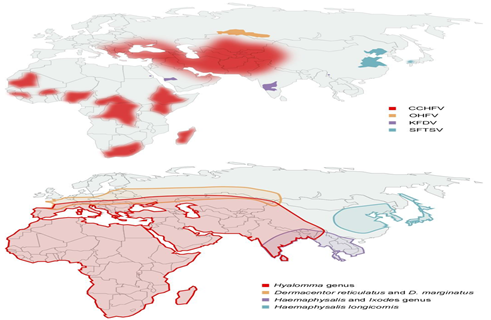

7. The Crimea-Congo Fever Virus is transmitted by ticks. It is similar to the Ebola and Marburg viruses in the way it progresses. During the first days of infection, sufferers present with pin-sized bleedings in the face, mouth and the pharynx.

Transmitted through tick bites this disease is endemic (consistently present) in most countries of West Africa and the Middle East. Although rare, CCHF has a 30% mortality rate. The most recent outbreak of the disease was in 2005 in Turkey. The Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever is a common disease transmitted by a tick-Bourne virus. The virus causes major hemorrhagic fever outbreaks with a fatality rate of up to 30%. It is chiefly transmitted to people through tick and livestock. Person-to-person transmission occurs through direct contact with the blood, secretions and other bodily fluids of an infected person. No vaccination exists for both humans and animals against CCHF.

8. The Machupo Virus is associated with Bolivian hemorrhagic fever, also known as black typhus. The infection causes high fever, accompanied by heavy bleedings. It progresses similar to the Junin virus. The virus can be transmitted from human to human, and rodents often the carry it.

Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (BHF), also known as black typhus or Ordog Fever, is a hemorrhagic fever and zoonotic infectious disease originating in Bolivia after infection by Machupo virus.BHF was first identified in 1963 as an ambisense RNA virus of the Arenaviridae family,by a research group led by Karl Johnson. The mortality rate is estimated at 5 to 30 percent.

Due to its pathogenicity, Machupo virus requires Biosafety Level Four conditions, the highest level.In February and March 2007, some 20 suspected BHF cases (3 fatal) were reported to the El Servicio Departmental de Salud (SEDES) in Beni Department, Bolivia, and in February 2008, at least 200 suspected new cases (12 fatal) were reported to SEDES.In November 2011, a SEDES expert involved in a serosurvey to determine the extent of Machupo virus infections in the Department after the discovery of a second confirmed case near the departmental capital of Trinidad in November, 2011, expressed concern about expansion of the virus' distribution outside the endemic zone in Mamoré and Iténez provinces.

Bolivian hemorrhagic fever was one of three hemorrhagic fevers and one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program. It was also under research by the Soviet Union, under the Biopreparat bureau.

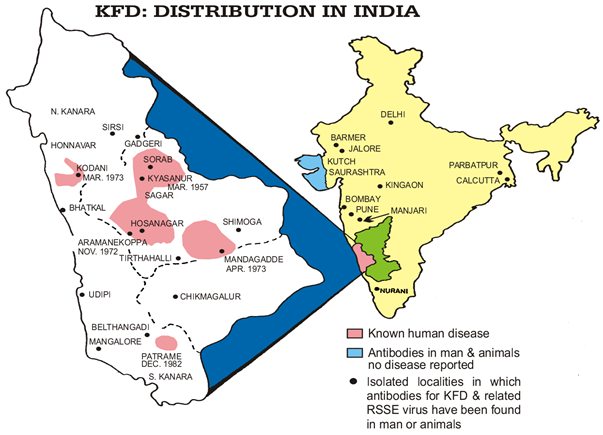

9. Kyasanur Forest Virus Scientists discovered the Kyasanur Forest Virus (KFD) virus in woodlands on the southwestern coast of India in 1955. It is transmitted by ticks, but scientists say it is difficult to determine any carriers. It is assumed that rats, birds and boars could be hosts. People infected with the virus suffer from high fever, strong headaches and muscle pain which can cause bleedings.

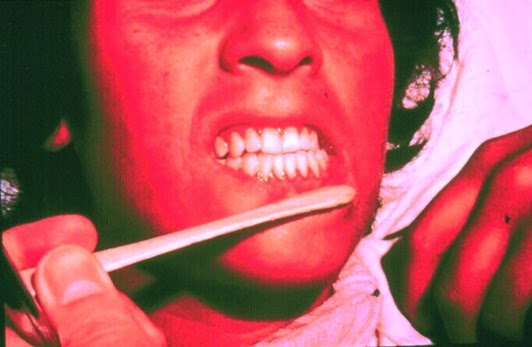

The disease has a morbidity rate of 2-10%, and affects 100-500 people annually.The symptoms of the disease include a high fever with frontal headaches, followed by hemorrhagic symptoms, such as bleeding from the nasal cavity, throat, and gums, as well as gastrointestinal bleeding.An affected person may recover in two weeks time, but the convalescent period is typically very long, lasting for several months. There will be muscle aches and weakness during this period and the affected person is unable to engage in physical activities.

There are a variety of animals thought to be reservoir hosts for the disease, including porcupines, rats, squirrels, mice and shrews. The vector for disease transmission is Haemaphysalis spinigera, a forest tick. Humans contract infection from the bite of nymphs of the tick.

The disease was first reported from Kyasanur Forest of Karnataka in India in March 1957. The disease first manifested as an epizootic outbreak among monkeys killing several of them in the year 1957. Hence the disease is also locally known as Monkey Disease or Monkey Fever. The similarity with Russian Spring-summer encephalitis was noted and the possibility of migratory birds carrying the disease was raised. Studies began to look for the possible species that acted as reservoirs for the virus and the agents responsible for transmission. Subsequent studies failed to find any involvement of migratory birds although the possibility of their role in initial establishment was not ruled out. The virus was found to be quite distinctive and not closely related to the Russian virus strains.

Antigenic relatedness is however close to many other strains including the Omsk hemorrhagic fever (OHF) and birds from Siberia have been found to show an antigenic response to KFD virus. Sequence based studies however note the distinctiveness of OHF.Early studies in India were conducted in collaboration with the US Army Medical Research Unit and this led to controversy and conspiracy theories.

Subsequent studies based on sequencing found that the Alkhurma virus, found in Saudi Arabia is closely related. In 1989 a patient in Nanjianin, China was found with fever symptoms and in 2009 its viral gene sequence was found to exactly match with that of the KFD reference virus of 1957. This has however been questioned since the Indian virus shows variations in sequence over time and the exact match with the virus sequence of 1957 and the Chinese virus of 1989 is not expected.

This study also found using immune response tests that birds and humans in the region appeared to have been exposed to the virus.Another study has suggested that the virus is recent in origin dating the nearest common ancestor of it and related viruses to around 1942, based on the estimated rate of sequence substitutions. The study also raises the possibility of bird involvement in long-distance transfer. It appears that these viruses diverged 700 years ago.

10. Dengue Fever is a constant threat. If you're planning a holiday in the tropics, get informed about dengue. Transmitted by mosquitoes, dengue affects between 50 and 100 million people a year in popular holiday destinations such as Thailand and India. But it's more of a problem for the 2 billion people who live in areas that are threatened by dengue fever.

25,000 Deaths a year Also known as ‘breakbone fever’ due to the extreme pain felt during fever, is an relatively new disease caused by one of four closely-related viruses. WHO estimates that a whopping 2.5 billion people (two fifths of the World’s population) are at risk from dengue. It puts the total number of infections at around 50 million per year, and is now epidemic in more than 100 countries.

Dengue viruses are transferred to humans through the bites of infective female Aedes mosquitoes. The dengue virus circulates in the blood of a human for two to seven days, during the same time they have the fever. It usually appears first on the lower limbs and the chest; in some patients, it spreads to cover most of the body. There may also be severe retro-orbital pain, (a pain from behind the eyes that is distinctive to Dengue infections), and gastritis with some combination of associated abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting coffee-grounds-like congealed blood, or severe diarrhea.

The leading cause of death in the tropics and subtropics is the infection brought on by the dengue virus, which causes a high fever, severe headache, and, in the worst cases, hemorrhaging. The good news is that it's treatable and not contagious. The bad news is there's no vaccine, and you can get it easily from the bite of an infected mosquito—which puts at least a third of the world's human population at risk. The CDC estimates that there are over 100 million cases of dengue fever each year. It's a great marketing tool for bug spray.

11. HIV 3.1 Million Lives a Year Human Immunodeficiency Virus has claimed the lives of more than 25 million people since 1981. HIV gets to the immune system by infecting important cells, including helper cells called CD4+ T cells, plus macrophanges and dendritic cells. Once the virus has taken hold, it systematically kills these cells, damaging the infected person’s immunity and leaving them more at risk from infections.

The majority of people infected with HIV go on to develop AIDS. Once a patient has AIDS common infections and tumours normally controlled by the CD4+ T cells start to affect the person.

In the latter stages of the disease, pneumonia and various types of herpes can infect the patient and cause death.

Human immunodeficiency virus infection / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a disease of the human immune system caused by infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The term HIV/AIDS represents the entire range of disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus from early infection to late stage symptoms. During the initial infection, a person may experience a brief period of influenza-like illness. This is typically followed by a prolonged period without symptoms. As the illness progresses, it interferes more and more with the immune system, making the person much more likely to get infections, including opportunistic infections and tumors that do not usually affect people who have working immune systems.

HIV is transmitted primarily via unprotected sexual intercourse (including anal and oral sex), contaminated blood transfusions, hypodermic needles, and from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding. Some bodily fluids, such as saliva and tears, do not transmit HIV. Prevention of HIV infection, primarily through safe sex and needle-exchange programs, is a key strategy to control the spread of the disease. There is no cure or vaccine; however, antiretroviral treatment can slow the course of the disease and may lead to a near-normal life expectancy. While antiretroviral treatment reduces the risk of death and complications from the disease, these medications are expensive and have side effects. Without treatment, the average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.

Genetic research indicates that HIV originated in west-central Africa during the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. AIDS was first recognized by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1981 and its cause—HIV infection—was identified in the early part of the decade. Since its discovery, AIDS has caused an estimated 36 million deaths worldwide (as of 2012). As of 2012, approximately 35.3 million people are living with HIV globally. HIV/AIDS is considered a pandemic—a disease outbreak which is present over a large area and is actively spreading.

HIV/AIDS has had a great impact on society, both as an illness and as a source of discrimination. The disease also has significant economic impacts. There are many misconceptions about HIV/AIDS such as the belief that it can be transmitted by casual non-sexual contact. The disease has also become subject to many controversies involving religion. It has attracted international medical and political attention as well as large-scale funding since it was identified in the 1980s

12. Rotavirus 61,000 Lives a Year According to the WHO, this merciless virus causes the deaths of more than half a million children every year. In fact, by the age of five, virtually every child on the planet has been infected with the virus at least once. Immunity builds up with each infection, so subsequent infections are milder. However, in areas where adequate healthcare is limited the disease is often fatal. Rotavirus infection usually occurs through ingestion of contaminated stool.

Because the virus is able to live a long time outside of the host, transmission can occur through ingestion of contaminated food or water, or by coming into direct contact with contaminated surfaces, then putting hands in the mouth.

Once it’s made its way in, the rotavirus infects the cells that line the small intestine and multiplies. It emits an enterotoxin, which gives rise to gastroenteritis.

13. Smallpox Officially eradicated - Due to it's long history, it impossible to estimate the carnage over the millennia Smallpox localizes in small blood vessels of the skin and in the mouth and throat. In the skin, this results in a characteristic maculopapular rash, and later, raised fluid-filled blisters. It has an overall mortality rate of 30–35%. Smallpox is believed to have emerged in human populations about 10,000 BC. The disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans per year during the closing years of the 18th century (including five reigning monarchs), and was responsible for a third of all blindness. Of all those infected, 20–60%—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease.

Smallpox was responsible for an estimated 300–500 million deaths during the 20th century alone. In the early 1950s an estimated 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year.

As recently as 1967, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 15 million people contracted the disease and that two million died in that year. After successful vaccination campaigns throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the WHO certified the eradication of smallpox in December 1979.

Smallpox is one of only two infectious diseases to have been eradicated by humans, the other being Rinderpest, which was unofficially declared eradicated in October 2010.

The virus that causes smallpox wiped out hundreds of millions of people worldwide over thousands of years. We can’t even blame it on animals either, as the virus is only carried by and contagious for humans. There are several different types of smallpox disease that result from an infection ranging from mild to fatal, but it is generally marked by a fever, rash, and blistering, oozing pustules that develop on the skin. Fortunately, smallpox was declared eradicated in 1979, as the result of successful worldwide implementation of the vaccine.

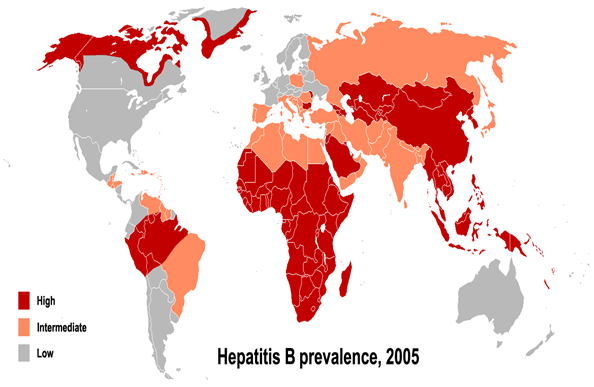

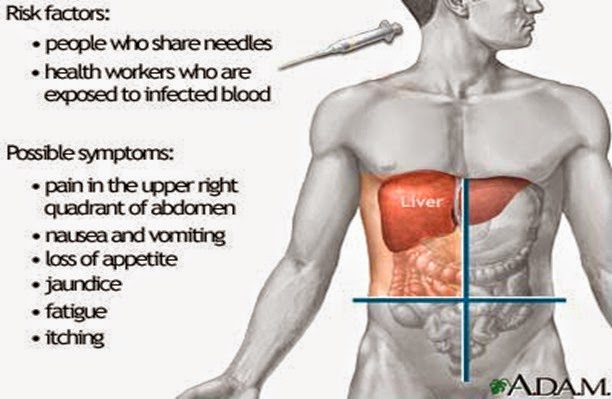

14. Hepatitis B 521,000 Deaths a Year A third of the World’s population (over 2 billion people) has come in contact with this virus, including 350 million chronic carriers. In China and other parts of Asia, up to 10% of the adult population is chronically infected. The symptoms of acute hepatitis B include yellowing of the skin of eyes, dark urine, vomiting, nausea, extreme fatigue, and abdominal pain.

Luckily, more than 95% of people who contract the virus as adults or older children will make a full recovery and develop immunity to the disease. In other people, however, hepatitis B can bring on chronic liver failure due to cirrhosis or cancer.

Hepatitis B is an infectious illness of the liver caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) that affects hominoidea, including humans. It was originally known as "serum hepatitis". Many people have no symptoms during the initial infected. Some develop an acute illness with vomiting, yellow skin, dark urine and abdominal pain. Often these symptoms last a few weeks and rarely result in death. It may take 30 to 180 days for symptoms to begin. Less than 10% of those infected develop chronic hepatitis B. In those with chronic disease cirrhosis and liver cancer may eventually develop.

The virus is transmitted by exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. Infection around the time of birth is the most common way the disease is acquired in areas of the world where is common. In areas where the disease is uncommon intravenous drug use and sex are the most common routes of infection. Other risk factors include working in a healthcare setting, blood transfusions, dialysis, sharing razors or toothbrushes with an infected person, travel in countries where it is common, and living in an institution.

Tattooing and acupuncture led to a significant number of cases in the 1980s; however, this has become less common with improved sterility. The hepatitis B viruses cannot be spread by holding hands, sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses, kissing, hugging, coughing, sneezing, or breastfeeding. The hepatitis B virus is a hepadnavirus—hepa from hepatotropic (attracted to the liver) and dna because it is a DNA virus. The viruses replicate through an RNA intermediate form by reverse transcription, which in practice relates them to retroviruses.It is 50 to 100 times more infectious than HIV.

The infection has been preventable by vaccination since 1982. During the initial infected care is based on the symptoms present. In those who developed chronic disease antiviral medication such as tenofovir or interferon maybe useful, however are expensive.

About a third of the world population has been infected at one point in their lives, including 350 million who are chronic carriers. Over 750,000 people die of hepatitis B a year. The disease has caused outbreaks in parts of Asia and Africa, and it is now only common in China. Between 5 and 10% of adults in sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia have chronic disease. Research is in progress to create edible HBV vaccines in foods such as potatoes, carrots, and bananas.In 2004, an estimated 350 million individuals were infected worldwide. National and regional prevalence ranges from over 10% in Asia to under 0.5% in the United States and northern Europe. Routes of infection include vertical transmission (such as through childbirth), early life horizontal transmission (bites, lesions, and sanitary habits), and adult horizontal transmission (sexual contact, intravenous drug use).

The primary method of transmission reflects the prevalence of chronic HBV infection in a given area. In low prevalence areas such as the continental United States and Western Europe, injection drug abuse and unprotected sex are the primary methods, although other factors may also be important. In moderate prevalence areas, which include Eastern Europe, Russia, and Japan, where 2–7% of the population is chronically infected, the disease is predominantly spread among children. In high-prevalence areas such as China and South East Asia, transmission during childbirth is most common, although in other areas of high endemicity such as Africa, transmission during childhood is a significant factor. The prevalence of chronic HBV infection in areas of high endemicity is at least 8% with 10-15% prevalence in Africa/Far East. As of 2010, China has 120 million infected people, followed by India and Indonesia with 40 million and 12 million, respectively. According to World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 600,000 people die every year related to the infection. In the United States about 19,000 new cases occurred in 2011 down nearly 90% from 1990.

Acute infection with hepatitis B virus is associated with acute viral hepatitis – an illness that begins with general ill-health, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, body aches, mild fever, and dark urine, and then progresses to development of jaundice. It has been noted that itchy skin has been an indication as a possible symptom of all hepatitis virus types. The illness lasts for a few weeks and then gradually improves in most affected people. A few people may have more severe liver disease (fulminant hepatic failure), and may die as a result. The infection may be entirely asymptomatic and may go unrecognized.

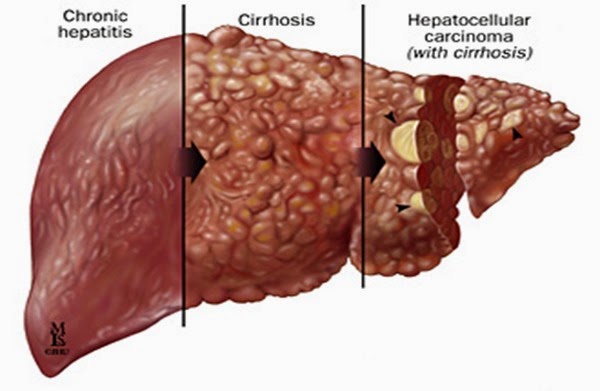

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus either may be asymptomatic or may be associated with a chronic inflammation of the liver (chronic hepatitis), leading to cirrhosis over a period of several years. This type of infection dramatically increases the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer). Across Europe hepatitis B and C cause approximately 50% of hepatocellular carcinomas. Chronic carriers are encouraged to avoid consuming alcohol as it increases their risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer. Hepatitis B virus has been linked to the development of membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN).

Symptoms outside of the liver are present in 1–10% of HBV-infected people and include serum-sickness–like syndrome, acute necrotizing vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa), membranous glomerulonephritis, and papular acrodermatitis of childhood (Gianotti–Crosti syndrome). The serum-sickness–like syndrome occurs in the setting of acute hepatitis B, often preceding the onset of jaundice. The clinical features are fever, skin rash, and polyarteritis. The symptoms often subside shortly after the onset of jaundice, but can persist throughout the duration of acute hepatitis B. About 30–50% of people with acute necrotizing vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa) are HBV carriers. HBV-associated nephropathy has been described in adults but is more common in children.Membranous glomerulonephritis is the most common form. Other immune-mediated hematological disorders, such as essential mixed cryoglobulinemia and aplastic anemia.

15. Influenza 500,000 Deaths a Year Influenza has been a prolific killer for centuries. The symptoms of influenza were first described more than 2,400 years ago by Hippocrates. Pandemics generally occur three times a century, and can cause millions of deaths. The most fatal pandemic on record was the Spanish flu outbreak in 1918, which caused between 20 million and 100 million deaths. In order to invade a host, the virus shell includes proteins that bind themselves to receptors on the outside of cells in the lungs and air passages of the victim. Once the virus has latched itself onto the cell it takes over so much of its machinery that the cell dies. Dead cells in the airways cause a runny nose and sore throat. Too many dead cells in the lungs causes death.

Vaccinations against the flu are common in developed countries. However, a vaccination that is effective one year may not necessarily work the next year, due to the way the rate at which a flu virus evolves and the fact that new strains will soon replace older ones. No virus can claim credit for more worldwide pandemics and scares than influenza.

The outbreak of the Spanish flu in 1918 is generally considered to be one of the worst pandemics in human history, infecting 20 to 40 percent of the world's population and killing 50 million in the span of just two years. (A reconstruction of that virus is above.) The swine flu was its most recent newsmaker, when a 2009 pandemic may have seen as many as 89 million people infected worldwide.

Effective influenza vaccines exist, and most people easily survive infections. But the highly infectious respiratory illness is cunning—the virus is constantly mutating and creating new strains. Thousands of strains exist at any given time, many of them harmless, and vaccines available in the U.S. cover only about 40 percent of the strains at large each year.

16. Hepatitis C 56,000 Deaths a Year An estimated 200-300 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C.

Most people infected with hepatitis C don’t have any symptoms and feel fine for years. However, liver damage invariably rears its ugly head over time, often decades after first infection. In fact, 70% of those infected develop chronic liver disease, 15% are struck with cirrhosis and 5% can die from liver cancer or cirrhosis. In the USA, hepatitis C is the primary reason for liver transplants.

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease affecting primarily the liver, caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). The infection is often asymptomatic, but chronic infection can lead to scarring of the liver and ultimately to cirrhosis, which is generally apparent after many years. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will go on to develop liver failure, liver cancer, or life-threatening esophageal and gastric varices.

HCV is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact associated with intravenous drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment, and transfusions. An estimated 150–200 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C. The existence of hepatitis C (originally identifiable only as a type of non-A non-B hepatitis) was suggested in the 1970s and proven in 1989. Hepatitis C infects only humans and chimpanzees.

The virus persists in the liver in about 85% of those infected. This chronic infection can be treated with medication: the standard therapy is a combination of peginterferon and ribavirin, with either boceprevir or telaprevir added in some cases. Overall, 50–80% of people treated are cured. Those who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer may require a liver transplant. Hepatitis C is the leading reason for liver transplantation, though the virus usually recurs after transplantation. No vaccine against hepatitis C is available.

Hepatitis C infection causes acute symptoms in 15% of cases. Symptoms are generally mild and vague, including a decreased appetite, fatigue, nausea, muscle or joint pains, and weight loss and rarely does acute liver failure result. Most cases of acute infection are not associated with jaundice. The infection resolves spontaneously in 10–50% of cases, which occurs more frequently in individuals who are young and female.

About 80% of those exposed to the virus develop a chronic infection. This is defined as the presence of detectable viral replication for at least six months. Most experience minimal or no symptoms during the initial few decades of the infection.Chronic hepatitis C can be associated with fatigue and mild cognitive problems. Chronic infection after several years may cause cirrhosis or liver cancer. The liver enzymes are normal in 7–53%. Late relapses after apparent cure have been reported, but these can be difficult to distinguish from reinfection.

Fatty changes to the liver occur in about half of those infected and are usually present before cirrhosis develops. Usually (80% of the time) this change affects less than a third of the liver. Worldwide hepatitis C is the cause of 27% of cirrhosis cases and 25% of hepatocellular carcinoma. About 10–30% of those infected develop cirrhosis over 30 years. Cirrhosis is more common in those also infected with hepatitis B, schistosoma, or HIV, in alcoholics and in those of male gender. In those with hepatitis C, excess alcohol increases the risk of developing cirrhosis 100-fold.Those who develop cirrhosis have a 20-fold greater risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. This transformation occurs at a rate of 1–3% per year. Being infected with hepatitis B in additional to hepatitis C increases this risk further.

Liver cirrhosis may lead to portal hypertension, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen), easy bruising or bleeding, varices (enlarged veins, especially in the stomach and esophagus), jaundice, and a syndrome of cognitive impairment known as hepatic encephalopathy. Ascites occurs at some stage in more than half of those who have a chronic infection.

The most common problem due to hepatitis C but not involving the liver is mixed cryoglobulinemia (usually the type II form) — an inflammation of small and medium-sized blood vessels. Hepatitis C is also associated with Sjögren's syndrome (an autoimmune disorder); thrombocytopenia; lichen planus; porphyria cutanea tarda; necrolytic acral erythema; insulin resistance; diabetes mellitus; diabetic nephropathy; autoimmune thyroiditis and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Thrombocytopenia is estimated to occur in 0.16% to 45.4% of people with chronic hepatitis C. 20–30% of people infected have rheumatoid factor — a type of antibody. Possible associations include Hyde's prurigo nodularis and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Cardiomyopathy with associated arrhythmias has also been reported. A variety of central nervous system disorders have been reported. Chronic infection seems to be associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

Persons who have been infected with hepatitis C may appear to clear the virus but remain infected. The virus is not detectable with conventional testing but can be found with ultra-sensitive tests.The original method of detection was by demonstrating the viral genome within liver biopsies, but newer methods include an antibody test for the virus' core protein and the detection of the viral genome after first concentrating the viral particles by ultracentrifugation. A form of infection with persistently moderately elevated serum liver enzymes but without antibodies to hepatitis C has also been reported. This form is known as cryptogenic occult infection.

Several clinical pictures have been associated with this type of infection. It may be found in people with anti-hepatitis-C antibodies but with normal serum levels of liver enzymes; in antibody-negative people with ongoing elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause; in healthy populations without evidence of liver disease; and in groups at risk for HCV infection including those on haemodialysis or family members of people with occult HCV. The clinical relevance of this form of infection is under investigation. The consequences of occult infection appear to be less severe than with chronic infection but can vary from minimal to hepatocellular carcinoma.

The rate of occult infection in those apparently cured is controversial but appears to be low 40% of those with hepatitis but with both negative hepatitis C serology and the absence of detectable viral genome in the serum have hepatitis C virus in the liver on biopsy.How commonly this occurs in children is unknown.

There is no cure, no vaccine.

17. Measle 197,000 Deaths a Year Measles, also known as Rubeola, has done a pretty good job of killing people throughout the ages. Over the last 150 years, the virus has been responsible for the deaths of around 200 million people. The fatality rate from measles for otherwise healthy people in developed countries is 3 deaths per thousand cases, or 0.3%. In underdeveloped nations with high rates of malnutrition and poor healthcare, fatality rates have been as high as 28%. In immunocompromised patients (e.g. people with AIDS) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.

During the 1850s, measles killed a fifth of Hawaii's people. In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population. In the 19th century, the disease decimated the Andamanese population. In 1954, the virus causing the disease was isolated from an 11-year old boy from the United States, David Edmonston, and adapted and propagated on chick embryo tissue culture.

To date, 21 strains of the measles virus have been identified.

18. Yellow Fever 30,000 Deaths a Year. Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease transmitted by the bite of female mosquitoes and is found in tropical and subtropical areas in South America and Africa. The only known hosts of the virus are primates and several species of mosquito. The origin of the disease is most likely to be Africa, from where it was introduced to South America through the slave trade in the 16th century. Since the 17th century, several major epidemics of the disease have been recorded in the Americas, Africa and Europe. In the 19th century, yellow fever was deemed one of the most dangerous infectious diseases.

Yellow fever presents in most cases with fever, nausea, and pain and it generally subsides after several days. In some patients, a toxic phase follows, in which liver damage with jaundice (giving the name of the disease) can occur and lead to death. Because of the increased bleeding tendency (bleeding diathesis), yellow fever belongs to the group of hemorrhagic fevers.

Since the 1980s, the number of cases of yellow fever has been increasing, making it a reemerging disease Transmitted through infected mosquitoes, Yellow Fever is still a serious problem in countries all over the world and a serious health risk for travelers to Africa, South America and some areas in the Caribbean. Fatality rates range from 15 to over 50%. Symptoms include high fever, headache, abdominal pain, fatigue, vomiting and nausea.

Yellow fever is a hemorrhagic fever transmitted by infected mosquitoes. The yellow is in reference to the yellow color (jaundice) that affects some patients. The virus is endemic in tropical areas in Africa and South America.

The disease typically occurs in two phases. The first phase typically causes fever, headache, muscle pain and back pain, chills and nausea. Most patients recover from these symptoms while 15% progresses to the toxic second phase. High fever returns, jaundice becomes apparent, patient complains of abdominal pain with vomiting, and bleeding in the mouth, eyes, nose or stomach occurs. Blood appears in the stool or vomit and kidney function deteriorates. 50% of the patients that enter the toxic phase die within 10 to 14 days.

There is no treatment for yellow fever. Patients are only given supportive care for fever, dehydration and respiratory failure. Yellow fever is preventable through vaccination.

19. Rabies 55,000 Deaths a Year Rabies is almost invariably fatal if post-exposure prophylaxis is not administered prior to the onset of severe symptoms. If there wasn't a vaccine, this would be the most deadly virus on the list.

It is a zoonotic virus transmitted through the bite of an animal. The virus worms its way into the brain along the peripheral nerves. The incubation phase of the rabies disease can take up to several months, depending on how far it has to go to reach the central nervous system. It provokes acute pain, violent movements, depression, uncontrollable excitement, and inability to swallow water (rabies is often known as ‘hydrophobia’). After these symptoms subside the fun really starts as the infected person experiences periods of mania followed by coma then death, usually caused by respiratory insufficiency.

Rabies has a long and storied history dating back to 2300 B.C., with records of Babylonians who went mad and died after being bitten by dogs. While this virus itself is a beast, the sickness it causes is now is wholly preventable if treated immediately with a series of vaccinations (sometimes delivered with a terrifyingly huge needle in the abdomen). We have vaccine inventor Louis Pasteur to thank for that.

Exposure to rabies these days, while rare in the U.S., still occurs as it did thousands of years ago—through bites from infected animals. If left untreated after exposure, the virus attacks the central nervous system and death usually results. The symptoms of an advanced infection include delirium, hallucinations and raging, violent behavior in some cases, which some have argued makes rabies eerily similar to zombification. If rabies ever became airborne, we might actually have to prepare for that zombie apocalypse after all.

21. Common Cold No known cure The common cold is the most frequent infectious disease in humans with on average two to four infections a year in adults and up to 6–12 in children. Collectively, colds, influenza, and other infections with similar symptoms are included in the diagnosis of influenza-like illness.

They may also be termed upper respiratory tract infections (URTI). Influenza involves the lungs while the common cold does not.

It's annoying as hell, but there's nothing to do but wave the white flag on this one.

Virus: Infinity. People: 0

22. Anthrax Anthrax is a diseased caused by a bacterium called Bacillus Anthracis. There are three types of anthrax, skin, lung, and digestive. Anthrax has lately become a major world issue for its ability to become an epidemic and spread quickly and easily among people through contact with spores.

It is important to know that Anthrax is not spread from person to person, but is through contact/handling of products containing spores. Flu like symptoms, nausea, and blisters are common symptoms of exposure. Inhalational anthrax and gastrointestinal anthrax are serious issue because of their high mortality rates ranging from 50 to 100%.

Anthrax is a severe infectious disease caused by the bacteria Bacillus anthracis. This type of bacteria produces spores that can live for years in the soil. Anthrax is more common in farm animals, though humans can get infected as well. Anthrax is not contagious. A person can get infected only when the bacteria gets into the skin, lungs or digestive tract.

There are three types of anthrax: skin anthrax, inhalation anthrax and gastrointestinal anthrax. Skin anthrax symptoms include fever, muscle aches, headache, nausea and vomiting. Inhalation anthrax begins with flu-like symptoms, which progresses with severe respiratory distress. Shock, coma and then death follows. Most patients do not recover even if given appropriate antibiotics due to the toxins released by the anthrax bacteria. Gastrointestinal anthrax symptoms include fever, nausea, abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea.

Anthrax is treated with antibiotics.

23. Malaria Malaria is a mosquito-borne illness caused by parasite. Although malaria can be prevented and treated, it is often fatal.

Each year about 1 million people die from Malaria. Common symptoms include fever, chills, headache. Sweats, and fatigue. Malaria is a serious disease caused by Plasmodium parasites that infects Anopheles mosquitoes which feeds on humans. Initial symptoms include high fever, shaking chills, headache and vomiting - symptoms that may be too mild to be identified as malaria. If not treated within 24 hours, it can progress to severe illnesses that could lead to death.

The WHO estimates that malaria caused 207,000,000 clinical episodes and 627,000 deaths, mostly among African children, in 2012. About 3.5 billion people from 167 countries live in areas at risk of malaria transmission.

24. Cholera Due to the severe dehydration it causes, if left untreated Cholera can cause death within hours. In 1991 a major outbreak occurred in South America though currently few cases are known outside of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Symptoms include severe diarrhea, vomiting and leg cramping. Cholera is usually contracted through ingestion of contaminated water or food. Cholera is an acute intestinal infection caused by a bacterium called Vibrio cholera. It has an incubation period of less than a day to five days and causes painless, watery diarrhea that quickly leads to severe dehydration and death if treatment is not promptly given.

Cholera remains a global problem and continues to be a challenge for countries where access to safe drinking water and sanitation is a problem.

25. Typhoid Fever Patients with typhoid fever sometimes demonstrate a rash of flat, rose-colored spots and a sustained fever of 103 to 104.

Typhoid is contracted through contact with the S. Typhi bacteria, which is carried by humans in both their blood stream and stool. Over 400 cases occur in the US, 20% of those who contract it die. Typhoid fever is a serious and potentially fatal disease caused by the bacterium Salmonella Typhi. This type of bacteria lives only in humans. People sick with typhoid fever carry the bacteria in their bloodstream and intestinal tract and transmit the bacteria through their stool.

A person can get typhoid fever by drinking or eating food contaminated with Salmonella Typhi or if contaminated sewage gets into the water used for drinking or washing dishes.

Typhoid fever symptoms include high fever, weakness, headache, stomach pains or loss of appetite. Typhoid fever is determined by testing the presence of Salmonella Typhi in the stool or blood of an infected person. Typhoid fever is treated with antibiotics.

26. SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and the MERS VIRUS A new Pneumonia disease that emerged in China in 2003. After news of the outbreak of SARS China tried to silence news about it both internal and international news , SARS spread rapidly, reaching neighboring countries Hong Kong and Vietnam in late February 2003, and then to other countries via international travelers.Canada Had a outbreak that was fairly well covered and cost Canada quite a bit financially

The last case of this epidemic occurred in June 2003. In that outbreak, 8069 cases arise that killed 775 people. There is speculation that this disease is Man-Made SARS, SARS has symptoms of flu and may include: fever, cough, sore throat and other non-specific symptoms.

The only symptom that is common to all patients was fever above 38 degrees Celsius. Shortness of breath may occur later. There is currently no vaccine for the disease so that countermeasures can only assist the breathing apparatus. The virus was said to be the Virus of the End Times

27. MERS(Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome) The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), also termed EMC/2012 (HCoV-EMC/2012), is positive-sense, single-stranded RNA novel species of the genus Betacoronavirus.

First called novel coronavirus 2012 or simply novel coronavirus, it was first reported in 2012 after genome sequencing of a virus isolated from sputum samples from patients who fell ill in a 2012 outbreak of a new flu.

As of June 2014, MERS-CoV cases have been reported in 22 countries, including Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Jordan, Qatar, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman, Algeria, Bangladesh, the Philippines (still MERS-free), Indonesia (none was confirmed), the United Kingdom, and the United States. Almost all cases are somehow linked to Saudi Arabia. In the same article it was reported that Saudi authorities’ errors in response to MERS-CoV were a contributing factor to the spread of this deadly virus.

27. Enterovirus (Brain Inflammation) Entero virus is a disease of the hands, feet and mouth, and we can not ignored occasional Brain Inflammation. Enterovirus attack symptoms are very similar to regular flu symptoms so its difficult to detect it, such as fever, sometimes accompanied by dizziness and weakness and pain.

Next will come the little red watery bumps on the palms and feet following oral thrush. In severe conditions, Enterovirus can attack the nerves and brain tissue to result in death.

The virus is easily spread through direct contact with patients. Children are the main victims of the spread of enterovirus in China. Since the first victim was found but reporting was delayed until several weeks later.

24 thousand people have contracted the enterovirus. More than 30 of them died mostly children. The virus is reported to have entered Indonesia and infecting three people in Sumatra. 2014Enterovirus 68 is presently spreading across North America mainly and started in the USA has probably spread to Canada and Mexico by now. Enterovirus 68’s spread is unprecedented up till now

28. The Black Plague The 1918 flu virus and HIV are the biggest killers of modern times. But back in the 14th century, the bacterium that causes bubonic plague, or the Black Death as it was also known, was the baddest bug of all. In just a few years, from 1347 to 1351, the plague killed off about 75,000,000 people worldwide, including one-third of the entire population of Europe at that time.

It spread through Asia, Italy, North Africa, Spain, Normandy, Switzerland, and eastward into Hungary. After a brief break, it crossed into England, Scotland, and then to Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland and Greenland.

Yersinia pestis, the plague bacteria

Courtesy of Neal Chamberlain

The plague bacterium is called Yersinia <yer-sin-ee-uh> pestis. There are two main forms of the disease. In the bubonic <boo-bah-nick> form, the bacteria cause painful swellings as large as an orange to form in the armpits, neck and groin. These swellings, or buboes, often burst open, oozing blood and pus. Blood vessels leak blood that puddles under the skin, giving the skin a blackened look. That’s why the disease became known as the Black Death. At least half of its victims die within a week.

The pneumonic <new-mon-ick> form of plague causes victims to sweat heavily and cough up blood that starts filling their lungs. Almost no one survived it during the plague years. Yersinia pestis is the deadliest microbe we’ve ever known, although HIV might catch up to it. Yersinia pestis is still around in the world. Fortunately, with bacteria-killing antibiotics and measures to control the pests—rats and mice—that spread the bacteria, we’ve managed to conquer this killer.

29. Human Papillomavirus Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a DNA virus from the papillomavirus family that is capable of infecting humans. Like all papillomaviruses, HPVs establish productive infections only in keratinocytes of the skin or mucous membranes.

Most HPV infections are subclinical and will cause no physical symptoms; however, in some people subclinical infections will become clinical and may cause benign papillomas (such as warts [verrucae] or squamous cell papilloma), or cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, oropharynx and anus.HPV has been linked with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition, HPV 16 and 18 infections are a cause of a unique type of oropharyngeal (throat) cancer and are believed to cause 70% of cervical cancer, which have available vaccines, see HPV vaccine.

More than 30 to 40 types of HPV are typically transmitted through sexual contact and infect the anogenital region. Some sexually transmitted HPV types may cause genital warts. Persistent infection with "high-risk" HPV types—different from the ones that cause skin warts—may progress to precancerous lesions and invasive cancer. High-risk HPV infection is a cause of nearly all cases of cervical cancer.However, most infections do not cause disease.

Seventy percent of clinical HPV infections, in young men and women, may regress to subclinical in one year and ninety percent in two years. However, when the subclinical infection persists—in 5% to 10% of infected women—there is high risk of developing precancerous lesions of the vulva and cervix, which can progress to invasive cancer. Progression from subclinical to clinical infection may take years; providing opportunities for detection and treatment of pre-cancerous lesions.

In more developed countries, cervical screening using a Papanicolaou (Pap) test or liquid-based cytology is used to detect abnormal cells that may develop into cancer. If abnormal cells are found, women are invited to have a colposcopy. During a colposcopic inspection, biopsies can be taken and abnormal areas can be removed with a simple procedure, typically with a cauterizing loop or, more commonly in the developing world—by freezing (cryotherapy).

Treating abnormal cells in this way can prevent them from developing into cervical cancer. Pap smears have reduced the incidence and fatalities of cervical cancer in the developed world, but even so there were 11,000 cases and 3,900 deaths in the U.S. in 2008. Cervical cancer has substantial mortality worldwide, there are an estimated 490,000 cases and 270,000 deaths each year.

It is true that infections caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) are not fatal, but chronic infection may result in cervical cancer. Apparently, HPV is responsible for almost all cervical cancers (approx. 99%). HPV results in 275,000 deaths per year.

30. Henipaviruses The genus Henipavirus comprises of 3 members which are Hendra virus (HeV), Nipah virus (NiV), and Cedar virus (CedPV). The second one was introduced in the middle of 2012, although affected no human, and is therefore considered harmless. The rest of the two viruses, however, are lethal with mortality rate up to 50-100%.

Hendra virus (originally Equine morbillivirus) was discovered in September 1994 when it caused the deaths of thirteen horses, and a trainer at a training complex in Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane in Queensland, Australia.

The index case, a mare, was housed with 19 other horses after falling ill, and died two days later. Subsequently, all of the horses became ill, with 13 dying. The remaining 6 animals were subsequently euthanized as a way of preventing relapsing infection and possible further transmission.The trainer, Victory ('Vic') Rail, and a stable hand were involved in nursing the index case, and both fell ill with an influenza-like illness within one week of the first horse’s death. The stable hand recovered while Mr Rail died of respiratory and renal failure. The source of the virus was most likely frothy nasal discharge from the index case.

A second outbreak occurred in August 1994 (chronologically preceding the first outbreak) in Mackay 1,000 km north of Brisbane resulting in the deaths of two horses and their owner. The owner, Mark Preston, assisted in necropsies of the horses and within three weeks was admitted to hospital suffering from meningitis. Mr Preston recovered, but 14 months later developed neurologic signs and died. This outbreak was diagnosed retrospectively by the presence of Hendra virus in the brain of the patient.

A survey of wildlife in the outbreak areas was conducted, and identified pteropid fruit bats as the most likely source of Hendra virus, with a seroprevalence of 47%. All of the other 46 species sampled were negative. Virus isolations from the reproductive tract and urine of wild bats indicated that transmission to horses may have occurred via exposure to bat urine or birthing fluids. However, the only attempt at experimental infection reported in the literature, conducted at CSIRO Geelong, did not result in infection of a horse from infected flying foxes. This study looked at potential infection between bats, horses and cats, in various combinations. The only species that was able to infect horses was the cat (Felix spp.)

Nipah virus was identified in April 1999, when it caused an outbreak of neurological and respiratory disease on pig farms in peninsular Malaysia, resulting in 257 human cases, including 105 human deaths and the culling of one million pigs. In Singapore, 11 cases, including one death, occurred in abattoir workers exposed to pigs imported from the affected Malaysian farms. The Nipah virus has been classified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a Category C agent. The name "Nipah" refers to the place, Kampung Baru Sungai Nipah in Negeri Sembilan State, Malaysia, the source of the human case from which Nipah virus was first isolated.

The outbreak was originally mistaken for Japanese encephalitis (JE), however, physicians in the area noted that persons who had been vaccinated against JE were not protected, and the number of cases among adults was unusual Despite the fact that these observations were recorded in the first month of the outbreak, the Ministry of Health failed to react accordingly, and instead launched a nationwide campaign to educate people on the dangers of JE and its vector, Culex mosquitoes.

Symptoms of infection from the Malaysian outbreak were primarily encephalitic in humans and respiratory in pigs. Later outbreaks have caused respiratory illness in humans, increasing the likelihood of human-to-human transmission and indicating the existence of more dangerous strains of the virus. Based on seroprevalence data and virus isolations, the primary reservoir for Nipah virus was identified as Pteropid fruit bats, including Pteropus vampyrus (Large Flying Fox), and Pteropus hypomelanus (Small flying fox), both of which occur in Malaysia.

The transmission of Nipah virus from flying foxes to pigs is thought to be due to an increasing overlap between bat habitats and piggeries in peninsular Malaysia. At the index farm, fruit orchards were in close proximity to the piggery, allowing the spillage of urine, feces and partially eaten fruit onto the pigs. Retrospective studies demonstrate that viral spillover into pigs may have been occurring in Malaysia since 1996 without detection. During 1998, viral spread was aided by the transfer of infected pigs to other farms, where new outbreaks occurred.

Cedar Virus (CedPV) was first identified in pteropid urine during work on Hendra virus undertaken in Queensland in 2009. Although the virus is reported to be very similar to both Hendra and Nipah, it does not cause illness in laboratory animals usually susceptible to paramyxoviruses. Animals were able to mount an effective response and create effective antibodies.

The scientists who identified the virus report:

- Hendra and Nipah viruses are 2 highly pathogenic paramyxoviruses that have emerged from bats within the last two decades. Both are capable of causing fatal disease in both humans and many mammal species. Serological and molecular evidence for henipa-like viruses have been reported from numerous locations including Asia and Africa, however, until now no successful isolation of these viruses have been reported. This paper reports the isolation of a novel paramyxovirus, named Cedar virus, from fruit bats in Australia. Full genome sequencing of this virus suggests a close relationship with the henipaviruses.Antibodies to Cedar virus were shown to cross react with, but not cross neutralize Hendra or Nipah virus. Despite this close relationship, when Cedar virus was tested in experimental challenge models in ferrets and guinea pigs, we identified virus replication and generation of neutralizing antibodies, but no clinical disease was observed. As such, this virus provides a useful reference for future reverse genetics experiments to determine the molecular basis of the pathogenicity of the henipaviruses.

30. Lyssaviruses This genus comprises of not only rabies virus (causing death of almost everyone who is infected) but certain other viruses such as Duvenhage virus, Mokola virus, and Australian bat lyssavirus. Although small number of cases are reported, but the ones reported have always been fatal. Bats are vectors for all of these types except for Mokola virus.

Lyssavirus (from Lyssa, the Greek goddess of madness, rage, and frenzy) is a genus of viruses belonging to the family Rhabdoviridae, in the order Mononegavirales. This group of RNA viruses includes the rabies virus traditionally associated with the disease. Viruses typically have either helical or cubic symmetry. Lyssaviruses have helical symmetry, so their infectious particles are approximately cylindrical in shape. This is typical of plant-infecting viruses. Human-infecting viruses more commonly have cubic symmetry and take shapes approximating regular polyhedra. The structure consists of a spiked outer envelope, a middle region consisting of matrix protein M, and an inner ribonucleocapsid complex region, consisting of the genome associated with other proteins.

Lyssavirus genome consists of a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA molecule that encodes five viral proteins: polymerase L, matrix protein M, phosphoprotein P, nucleoprotein N, and glycoprotein G.

Based on recent phylogenetic evidence, lyssa viruses are categorized into seven major species. In addition, five species recently have been discovered: West Caucasian bat virus, Aravan virus, Khuj and virus, Irkut virus and Shimoni bat virus. The major species include rabies virus (species 1), Lagos bat virus (species 2), Mokola virus (species 3), Duvenhage virus (species 4), European Bat lyssaviruses type 1 and 2 (species 5 and 6), and Australian bat lyssavirus (species 7).

Based on biological properties of the viruses, these species are further subdivided into phylogroups 1 and 2. Phylogroup 1 includes genotypes 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7, while phylogroup 2 includes genotypes 2 and 3. The nucleocapsid region of lyssavirus is fairly highly conserved from genotype to genotype across both phylogroups; however, experimental data have shown the lyssavirus strains used in vaccinations are only from the first species(i.e. classic rabies).

31. Tuberculosis Mucous, fever, fatigue, excessive sweating and weight loss. What do they all have in common?

They are symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, or TB. TB is a contagious bacterial infection that involves the lungs, but it may spread to other organs. The symptoms of this disease can remain stagnant for years or affect the person right away. People at higher risk for contracting TB include the elderly, infants and those with weakened immune systems due to other diseases, such as AIDS or diabetes, or even individuals who have undergone chemotherapy.

Being around others who may have TB, maintaining a poor diet or living in unsanitary conditions are all risk factors for contracting TB. In the United States, there are approximately 10 cases of TB per 100,000 people. Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB (short for tubercle bacillus), in the past also called phthisis, phthisis pulmonalis, or consumption, is a widespread, and in many cases fatal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis typically attacks the lungs, but can also affect other parts of the body. It is spread through the air when people who have an active TB infection cough, sneeze, or otherwise transmit respiratory fluids through the air. Most infections do not have symptoms, known as latent tuberculosis. About one in ten latent infections eventually progresses to active disease which, if left untreated, kills more than 50% of those so infected.

The classic symptoms of active TB infection are a chronic cough with blood-tinged sputum, fever, night sweats, and weight loss (the latter giving rise to the formerly common term for the disease, "consumption"). Infection of other organs causes a wide range of symptoms. Diagnosis of active TB relies on radiology (commonly chest X-rays), as well as microscopic examination and microbiological culture of body fluids.

Diagnosis of latent TB relies on the tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or blood tests. Treatment is difficult and requires administration of multiple antibiotics over a long period of time. Social contacts are also screened and treated if necessary. Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem in multiple drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) infections. Prevention relies on screening programs and vaccination with the bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine.

One-third of the world's population is thought to have been infected with M. tuberculosis, with new infections occurring in about 1% of the population each year.In 2007, an estimated 13.7 million chronic cases were active globally, while in 2010, an estimated 8.8 million new cases and 1.5 million associated deaths occurred, mostly in developing countries. The absolute number of tuberculosis cases has been decreasing since 2006, and new cases have decreased since 2002.

The rate of tuberculosis in different areas varies across the globe; about 80% of the population in many Asian and African countries tests positive in tuberculin tests, while only 5–10% of the United States population tests positive. More people in the developing world contract tuberculosis because of a poor immune system, largely due to high rates of HIV infection and the corresponding development of AIDS.

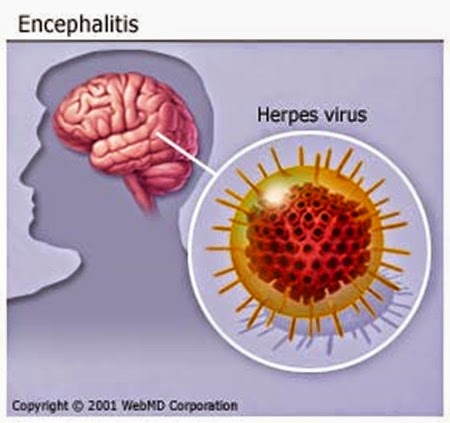

32. Encephalitis Virus Encephalitis is an acute inflammation of the brain, commonly caused by a viral infection. Victims are usually exposed to viruses resulting in encephalitis by insect bites or food and drink. The most frequently encountered agents are arboviruses (carried by mosquitoes or ticks) and enteroviruses ( coxsackievirus, poliovirus and echovirus ). Some of the less frequent agents are measles, rabies, mumps, varicella and herpes simplex viruses.

Patients with encephalitis suffer from fever, headache, vomiting, confusion, drowsiness and photophobia. The symptoms of encephalitis are caused by brain's defense mechanisms being activated to get rid of infection (brain swelling, small bleedings and cell death). Neurologic examination usually reveals a stiff neck due to the irritation of the meninges covering the brain. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluidCerebrospinal fluid CSF in short, is the clear fluid that occupies the subarachnoid space (the space between the skull and cortex of the brain). It acts as a "cushion" or buffer for the cortex.

Also, CSF occupies the ventricular system of the brain and the obtained by a lumbar puncture In medicine, a lumbar puncture (colloquially known as a spinal tap is a diagnostic procedure that is done to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for biochemical, microbiological and cytological analysis. Indications The most common indication for procedure reveals increased amounts of proteins and white blood cells with normal glucose. A CT scan examination is performed to reveal possible complications of brain swelling, brain abscess Brain abscess (or cerebral abscess) is an abscess caused by inflammation and collection of infected material coming from local (ear infection, infection of paranasal sinuses, infection of the mastoid air cells of the temporal bone, epidural abscess) or re or bleeding. Lumbar puncture procedure is performed only after the possibility of a prominent brain swelling is excluded by a CT scan examination.

What are the main Symptoms?

Some patients may have symptoms of a cold or stomach infection before encephalitis symptoms begin.

When a case of encephalitis is not very severe, the symptoms may be similar to those of other illnesses, including:

• Fever that is not very high

• Mild headache

• Low energy and a poor appetite

Other symptoms include:

• Clumsiness, unsteady gait

• Confusion, disorientation

• Drowsiness

• Irritability or poor temper control

• Light sensitivity

• Stiff neck and back (occasionally)

• Vomiting

Symptoms in newborns and younger infants may not be as easy to recognize:

• Body stiffness

• Irritability and crying more often (these symptoms may get worse when the baby is picked up)

• Poor feeding

• Soft spot on the top of the head may bulge out more

• Vomiting

• Loss of consciousness, poor responsiveness, stupor, coma

• Muscle weakness or paralysis

• Seizures

• Severe headache

• Sudden change in mental functions:

• "Flat" mood, lack of mood, or mood that is inappropriate for the situation

• Impaired judgment

• Inflexibility, extreme self-centeredness, inability to make a decision, or withdrawal from social interaction

• Less interest in daily activities

• Memory loss (amnesia), impaired short-term or long-term memory

Children and adults should avoid contact with anyone who has encephalitis.

Controlling mosquitoes (a mosquito bite can transmit some viruses) may reduce the chance of some infections that can lead to encephalitis.

• Apply an insect repellant containing the chemical, DEET when you go outside (but never use DEET products on infants younger than 2 months).

• Remove any sources of standing water (such as old tires, cans, gutters, and wading pools).

• Wear long-sleeved shirts and pants when outside, particularly at dusk.

Vaccinate animals to prevent encephalitis caused by the rabies virus.

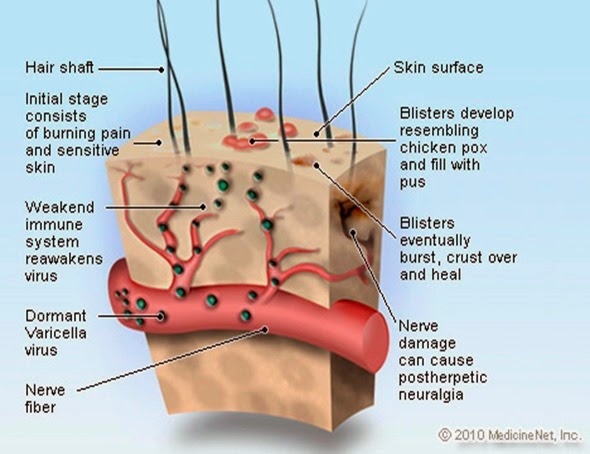

33. Chicken Pox Virus Chickenpox is a highly contagious disease caused by primary infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV).It usually starts with a vesicular skin rash mainly on the body and head rather than on the limbs. The rash develops into itchy, raw pockmarks, which mostly heal without scarring. On examination, the observer typically finds skin lesions at various stages of healing and also ulcers in the oral cavity and tonsil areas. The disease is most commonly observed in children.