What Are the Chances Ebola Will Spread in the United States?

What Are the Chances Ebola Will Spread in the United States?

UPDATED OCT. 3, 2014

Health officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said they were confident that standard procedures for controlling an infection will contain Ebola in the United States. The C.D.C. has sent experts to Texas to trace anyone who may have come in contact with the patient while he was contagious.

Doctors across the country are being reminded to ask for the travel history of anybody who comes in with a fever. Patients who have been to West Africa are being screened and tested if there seems to be a chance they have been exposed.

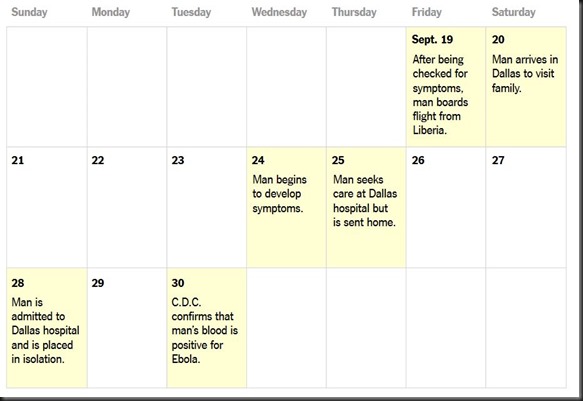

When did the man infected with Ebola arrive in the U.S.?

Thomas E. Duncan, who traveled to Dallas from Liberia, has been found to have Ebola, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported on Tuesday. He was screened for fever before boarding the plane — a standard airport procedure in Liberia — and showed no symptoms at that time.

Man is admitted to Dallas hospital and is placed in isolation.

C.D.C. confirms that man’s blood is positive for

Ebola.

How do officials in the U.S. keep Ebola from spreading?

Health officials use contact tracing, which means they identify everyone who might have been exposed to the patient during the time he was infectious, and then monitor them for symptoms every day for 21 days. Most people develop symptoms within eight to 10 days of being exposed. Anyone who starts running a fever or having symptoms is isolated and tested for Ebola. If the test is positive, that person is kept in isolation and treated, and his or her contacts are then traced for 21 days. The process is repeated until there are no new cases.

Are there drugs to treat or prevent Ebola?

There are currently no drugs or vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat or prevent Ebola. An experimental drug called ZMapp might help infected patients, but the drug is unproven and only available in limited quantities. The World Health Organization suggests that blood from Ebola survivors might be used to treat others, but there is no proof that such a treatment alone would work for Ebola.

Officials have emphasized that people are infectious only if they have symptoms of Ebola. There is no risk of transmission from people who have been exposed to the virus but are not yet showing symptoms. Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said the odds of contracting Ebola in the United States were still extremely low.

Ebola spreads through direct contact with body fluids. If an infected person’s blood or vomit gets in another person’s eyes, nose or mouth, the virus may be transmitted. Ebola does not invade through healthy skin, but skin must be sanitized after potential contact to avoid spreading the virus by touch. Although Ebola does not cause respiratory problems, a cough from a sick person could infect someone who has been sprayed with saliva. Because of that, being within three feet of a patient for a prolonged time without protective clothing is considered to be direct contact.

The virus can survive for several hours on surfaces, so any object contaminated with bodily fluids, like a latex glove or a hypodermic needle, may spread the disease. According to the C.D.C., the virus can survive for a few hours on dry surfaces like doorknobs and countertops. But it can survive for several days in puddles or other collections of body fluid at room temperature. Bleach solutions can kill it.

In the current outbreak, most new cases are occurring among people who have been taking care of sick relatives or who have prepared an infected body for burial. Health care workers are at high risk, especially if they have not been properly equipped with protective gear or correctly trained to use and decontaminate it.

It helps that Ebola does not spread nearly as easily as Hollywood movies about contagious diseases might suggest. In 2008, a patient who had contracted Marburg – a virus much like Ebola – in Uganda was treated at a hospital in the United States and could have exposed more than 200 people to the disease before anyone would have known what she had. Yet no one became sick.

How does the disease progress?

Symptoms usually begin about eight to 10 days after exposure to the virus, but can appear as late as 21 days after exposure, according to the C.D.C. At first, it seems much like the flu: a headache, fever and aches and pains. Sometimes there is also a rash. Diarrhea and vomiting follow.

Then, in about half of the cases, Ebola takes a severe turn, causing victims to hemorrhage. They may vomit blood or pass it in urine, or bleed under the skin or from their eyes or mouths. But bleeding is not usually what kills patients. Rather, blood vessels deep in the body begin leaking fluid, causing blood pressure to plummet so low that the heart, kidneys, liver and other organs begin to fail.

How many people have been infected?

More than 7,400 people in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Senegal and Sierra Leone have contracted Ebola since March, according to the World Health Organization, making this the biggest outbreak on record. More than 3,400 people have died. In the first case diagnosed in the United States, a man who traveled from Liberia to Dallas tested positive for the virus on Sept. 30.

The disease continues to spread in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. The C.D.C. said Tuesday that Nigeria appears to have contained its outbreak.

How big can the outbreak become?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on Sept. 23 that in a worst-case scenario, cases could reach 1.4 million in four months. The centers' model is based on data from August and includes cases in Liberia and Sierra Leone, but not Guinea (where counts have been unreliable).

Estimates are in line with those made by other groups like the World Health Organization, though the C.D.C. has projected further into the future and offered ranges that account for underreporting of cases.

Assumes 70 percent of patients are treated in settings that confine the illness and that the dead are buried safely. About 18 percent of patients in Liberia and 40 percent in Sierra Leone are being treated in appropriate settings.

If the disease continues spreading without effective intervention. Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the C.D.C. director, said, “My gut feeling is, the actions we’re taking now are going to make that worst-case scenario not come to pass. But it’s important to understand that it could happen.”

What is the United States doing to help?

President Obama announced Sept. 16 an expansion of military and medical resources to combat the outbreak, including the deployment of as many as 4,000 American military personnel to Liberia and Senegal. He said the United States would help Liberia in the construction of more than 17 Ebola treatment centers in the region, with about 1,700 beds, and would also open a joint command operation to coordinate the international effort to combat the disease. But military planners say construction of the centers have been delayed because of the difficulty in getting heavy equipment to the areas.

How does this compare to past outbreaks?

It is the deadliest, eclipsing an outbreak in 1976, the year the virus was discovered.

Ebola cases and deaths by year, and countries affected

Why is Ebola so difficult to contain?

The epidemic is growing faster than efforts to keep up with it, and it will take months before governments and health workers in the region can get the upper hand, according to Doctors Without Borders.

In some parts of West Africa, there is a belief that simply saying “Ebola” aloud makes the disease appear. Such beliefs have created major obstacles for physicians trying to combat the outbreak. Some people have even blamed physicians for the spread of the virus, opting to turn to witch doctors for treatment instead. Their skepticism is not without a grain of truth: In past outbreaks, hospital staff members who did not take thorough precautions became unwitting travel agents for the virus.

Ahmed Jallanzo/European Pressphoto Agency

Liberian health workers on the way to bury a woman who died of the Ebola virus.

There is no vaccine or definitive cure for Ebola, and in past outbreaks the virus has been fatal in 60 percent to 90 percent of cases. The United States government plans to fast-track development of a vaccine shown to protect macaque monkeys, but there is no guarantee it will be effective in humans. The question of who should have access to the scarce supplies of an experimental medicine has become a hotly debated ethical question. Beyond this, all physicians can do is try to nurse people through the illness, using fluids and medicines to maintain blood pressure, and treat other infections that often strike their weakened bodies. A small percentage of people appear to have an immunity to the Ebola virus.

Where does the disease come from?

Ebola was discovered in 1976, and it was once thought to originate in gorillas, because human outbreaks began after people ate gorilla meat. But scientists have since ruled out that theory, partly because apes that become infected are even more likely to die than humans.

Scientists now believe that bats are the natural reservoir for the virus, and that apes and humans catch it from eating food that bats have drooled or defecated on, or by coming in contact with surfaces covered in infected bat droppings and then touching their eyes or mouths.

The current outbreak seems to have started in a village near Guéckédou, Guinea, where bat hunting is common, according to Doctors Without Borders.

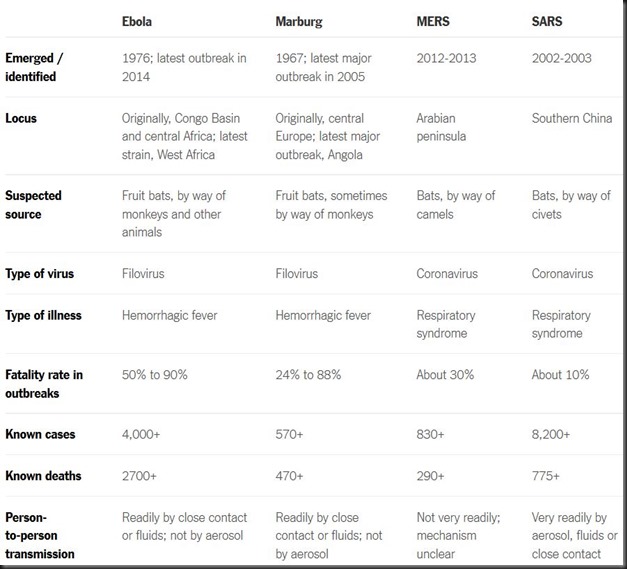

How does Ebola compare with other infectious diseases in the news?

The biggest headlines have tended to involve outbreaks of deadly viruses that medical workers have few, if any, tools to combat. The four most prominent are compared below. No cure is known for any of them, nor has any vaccine yet been approved for human use.

Note: On Sept. 30, officials with the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Mr. Duncan first went to the hospital on Sept. 26. On Oct. 1, the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital issued a statement that he first arrived there after 10 p.m. on Sept. 25.

By Jeremy Ashkenas, Larry Buchanan, Joe Burgess, Denise Grady, Josh Keller, Patrick J. Lyons, Heather Murphy, Haeyoun Park, Sergio Peçanha and Karen Yourish.

Comments

Post a Comment